Pam Hawley Marlin May 2019

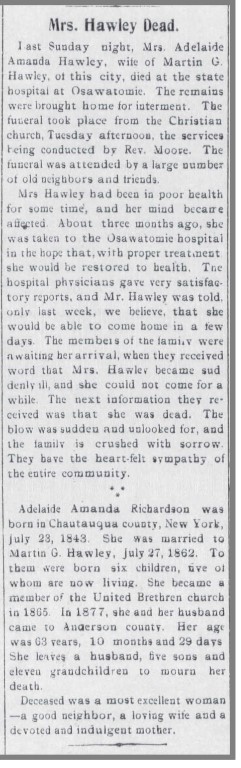

My family connection to Osawatomie State Hospital was first realized when I traveled to Garnett, Kansas for my first on-site research genealogy trip in 1986. When I arrived in Garnett, I visited the city cemetery to search for the gravesites of my great-great-great grandparents, Martin and Adelaide Hawley. After not being able to locate their gravesites, I visited the city office to view a map of the cemetery and found that both grandparents were indeed buried in the cemetery, however, they had no tombstone. The map also provided the death locations for both grandparents. Interestingly, the map suggested that my 3rd great-grandmother, Adelaide Amanda Hawley, had died at the Osawatomie State Hospital in Osawatomie, Kansas in 1906.

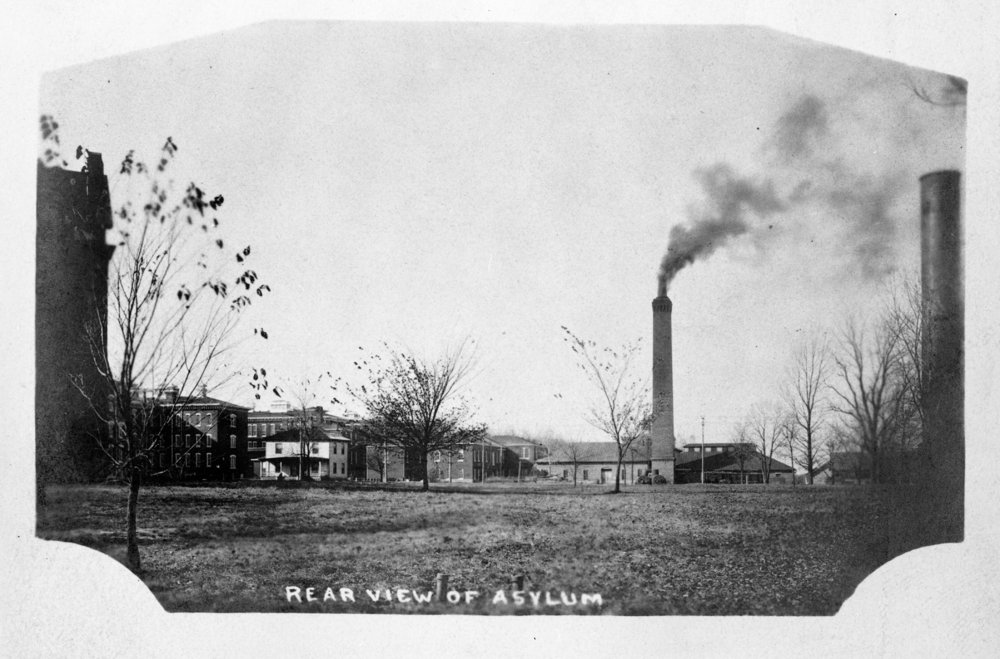

A view of the main administration building of the Osawatomie

State Hospital. 1900-1930.

Kansas Memory

A view of the main administration building of the Osawatomie

State Hospital. 1900-1930.

Kansas Memory

Osawatomie State Hospital when I first saw it in 1986.

Osawatomie State Hospital when I first saw it in 1986.

Osawatomie State Hospital main administration building after the

east and west wings were demolished.

Osawatomie State Hospital main administration building after the

east and west wings were demolished.

The initial step toward the establishment of an asylum for the insane of Kansas was the passage of the act of March 2, 1863, naming William Chestnut of Miami county, I. Hiner of Anderson county, and James Hanway of Franklin county as commissioners "to determine the location of the State Insane Asylum of the State of Kansas." The commissioners were somewhat restricted in the selection of a site, the act confining them to "some point within the township of Osawatomie township, in the county of Miami."1

The first Kansas State Insane Asylum was established a mile north of the town of Osawatomie, near the Marais des Cygnes River. The first section of land was donated by the people of Osawatomie, with additional land purchases made by the state of Kansas giving the hospital a full section of land.

An excerpt from the The Weekly Commonwealth on January 6, 1876, "In the first period in the history of the treatment of our insane the means employed were quite limited. The legislature passed a bill in 1863, the year of the Quantrell raid, forth establishment of an insane asylum at Osawatomie, but it was not until 1866 that the institution was opened, and in January 1867, it had but four inmates. The old frame farm house was the first asylum. With the exception of gratings at the windows, it was like any other farm house." 6

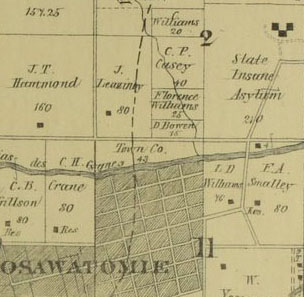

The plot of land where the asylum is located is in the north

east corner of an 1878 plat map of Osawatomie.

The plot of land where the asylum is located is in the north

east corner of an 1878 plat map of Osawatomie.

In 1866, the first building on the newly designated land was a small two-story frame structure that cost about $500. Called "The Lodge," it contained eight rooms and was intended to house 10 to 12 patients. Later that year, the asylum opened to receive its first patients. The first superintendent of the asylum was Dr. Charles O. Gause, and his wife, Mrs. Levisa Gause, served as matron.

Photo of the original asylum building called "The Lodge" in

Osawatomie, Kansas, 1866.

Kansas Memory

Photo of the original asylum building called "The Lodge" in

Osawatomie, Kansas, 1866.

Kansas Memory

Photo of the original asylum building called "The Lodge" in

Osawatomie, Kansas, 1866.

Kansas Memory

Photo of the original asylum building called "The Lodge" in

Osawatomie, Kansas, 1866.

Kansas Memory

As the Asylum grew, "The Lodge" was moved and used by a farmer

who worked at the asylum. It was also

used as an isolation unit for small pox before being torn down.

As the Asylum grew, "The Lodge" was moved and used by a farmer

who worked at the asylum. It was also

used as an isolation unit for small pox before being torn down.

An excerpt from the The Emporia News from November 6, 1868, describes the asylum surroundings:

"The Asylum is located on a fine farm of some 170 acres, and occupies most commanding site overlooking the whole country for miles in every direction. It is on the high land north of the Marias des Cygnes, and about two and a half miles from the village of Osawatomie. It overlooks old John Brown's famous battle-field, and from the cupola of the building, Osawatomie, Paola, Stanton and other points can be distinctly seen. The State affords no finer location." 3

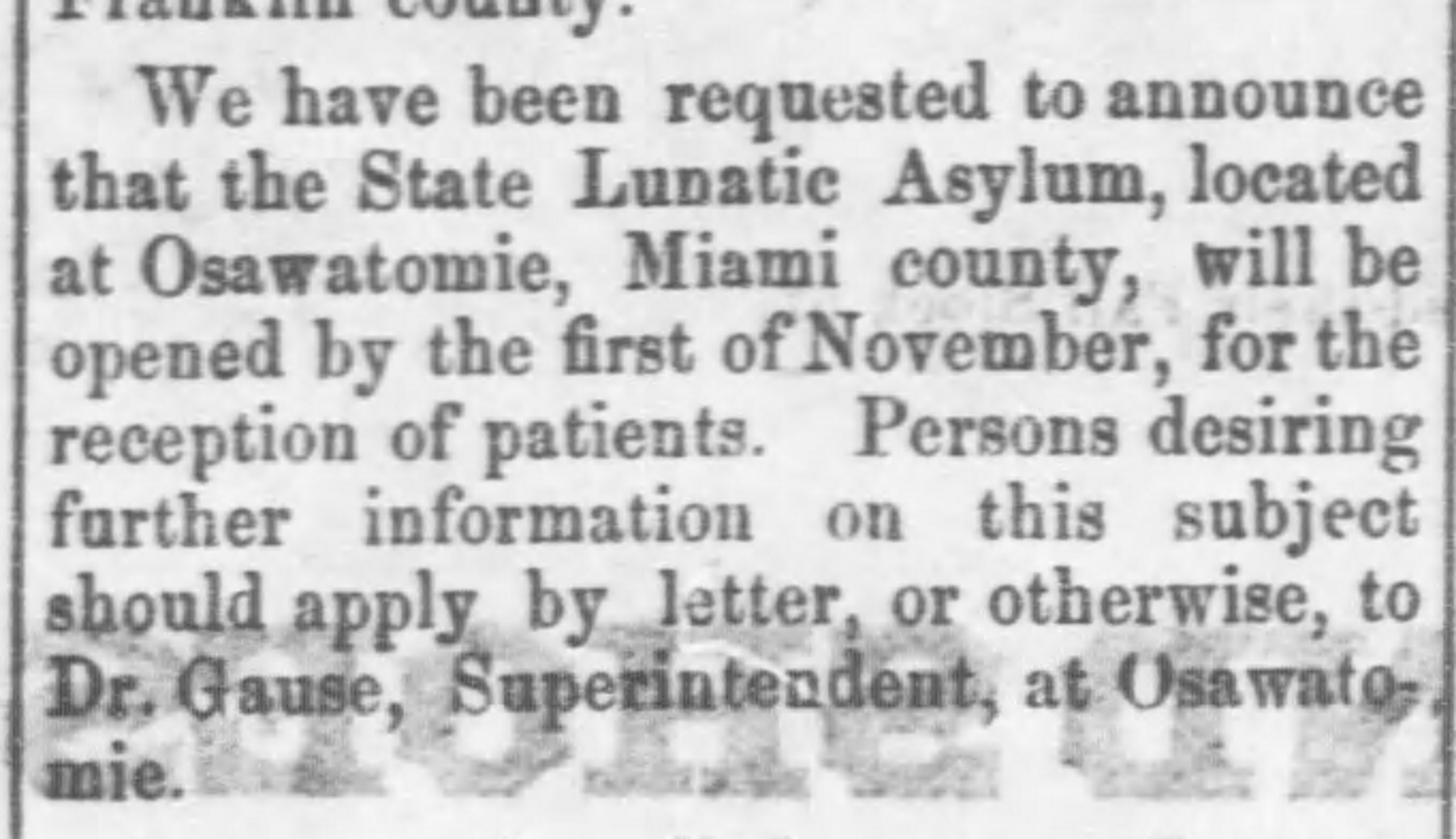

The official opening of the first Kansas Hospital for the Insane, also called the State Lunatic Asylum or State Insane Asylum, was on November 1, 1866:

"On that day, a small group of people assembled to participate in the opening and hear Reverend Samuel Adair of the Osawatomie Congressional Church pray for the well-being of the institution and all persons associated with it. The first patient was admitted four days later." 2

An announcement in the Daily Kansas Tribune on October

20, 1866.

An announcement in the Daily Kansas Tribune on October

20, 1866.

An excerpt from Reform at Osawatomie State Hospital describes the first patients' arrival at the asylum. The references below are from the notes taken by the first superintendent, Dr. Charles Gause.

"On November 5, 1866, a sullen, somewhat belligerent young man was escorted, with some force, into the renovated farmhouse on a hill above Osawatomie. He had been brought from the most populous Kansas community, Leavenowrth City, by a policeman. The beginning of the Kansas state insane asylum might be marked at the moment the twenty-one year old youth was dragged, swearing and using vulgar language, across the frame structure's doorsill. Two days later at 7:00am, the asylum's only inmate departed." 2

On November 15, 1866, a second patient from Leavenworth City entered the asylum. "On this date a sixty year old pioneer woman who had mothered seven children was, through deception, brought to the asylum." 2

A seven year old girl was admitted "on April 27, 1867, with the nature of her illness listed as feeble minded, and the cause as brain fever." The patient was discharged in October, but admitted again in July 1872, then again discharged. 2

At the time, many believed that the mentally ill were insensitive to cold or pain, as described in the seventh patient's arrival, "Was brought here in a wagon tied hand and foot. Had bene hauled in this condition from home, a distance of over one hundred miles in very cold weather. Was very exhausted... has bene improving. Is very cherefull and well satisfied with his new home." 2

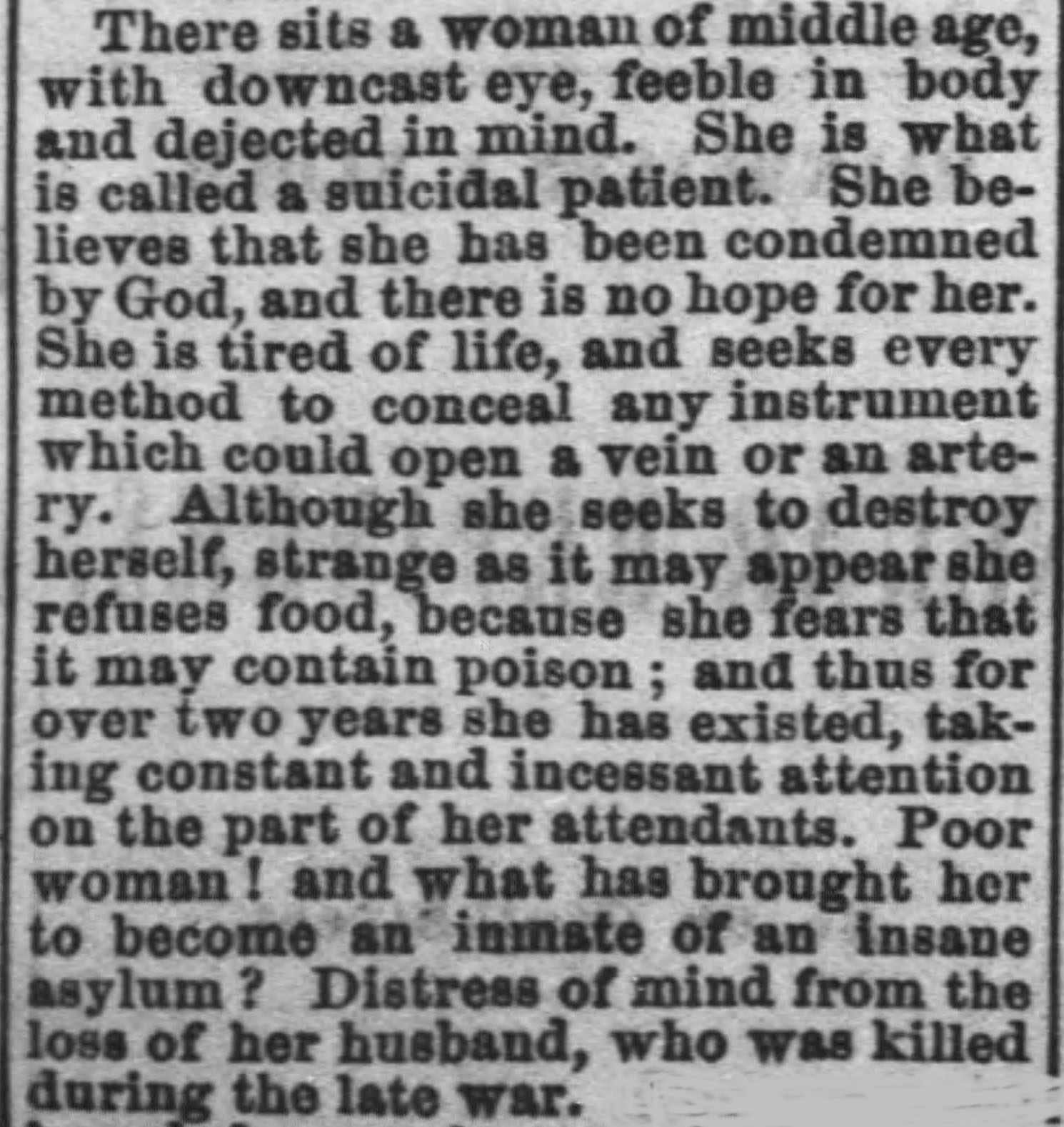

A suicidal patient in 1871:

From the Lawrence Daily Journal.

From the Lawrence Daily Journal.

Some patients experienced happy endings. In 1871, a young married woman was brought by her husband to the asylum as described in The Lawrence Daily Journal:

June 17, 1871, "she was confined within the folds of a military blanket, and around it was tied a cord, to confine the hands and limbs - without shoes or stockings, clothes torn and tattered, hair in wild disorder. In this condition she arrived. I witnessed her departure last Monday; her husband had been notified of her recovery, and he came to take her home. Their meeting together can only be imagined; no words can describe the joy and gratification of again meeting under such opposite circumstances as when they last parted."

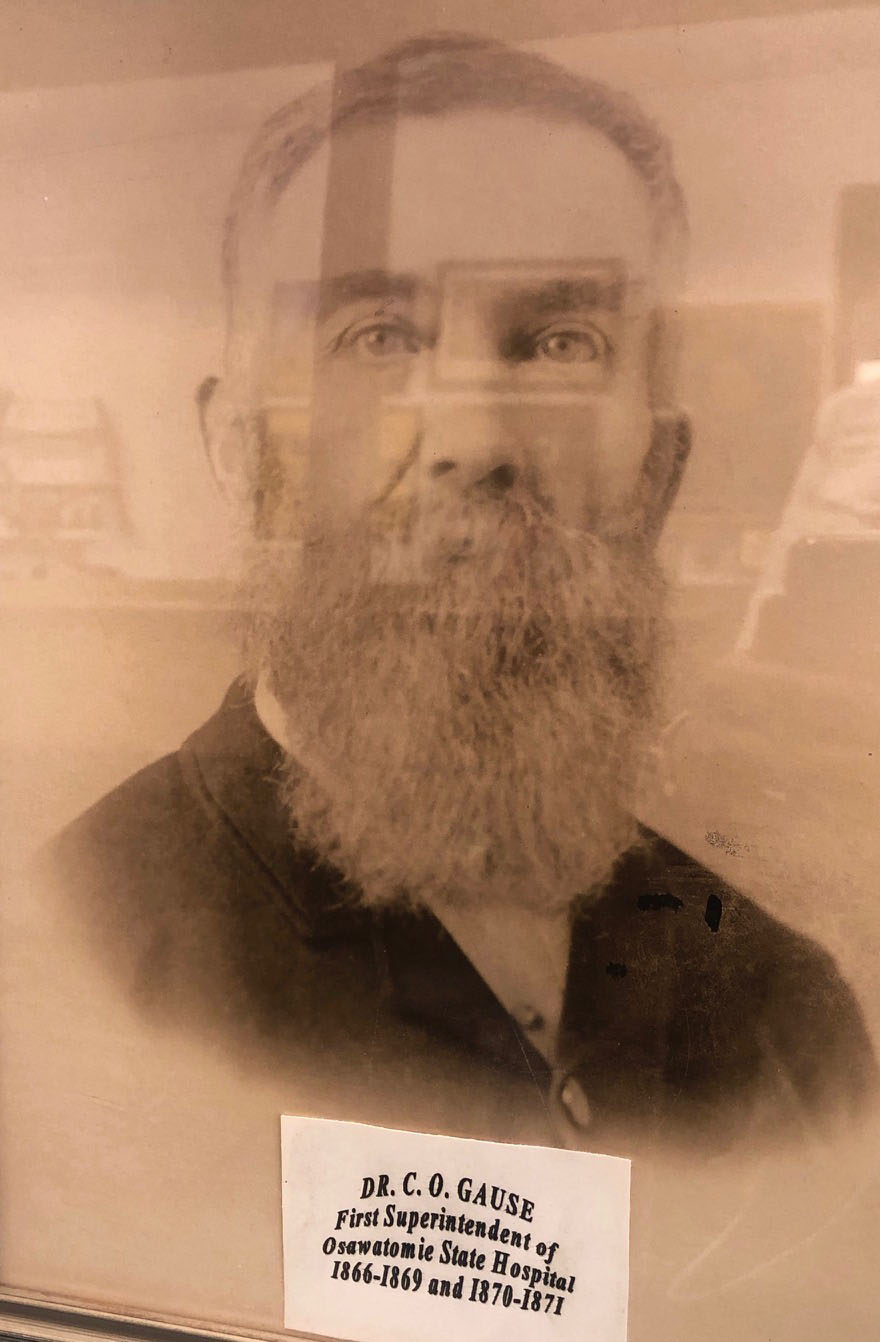

Dr. Charles O. Gause, the first superintendent of the Kansas State Insane Asylum, was known as the "tall, kindly physician with the heavy beard who had a reputation for calm but forceful determination." Known as a true "pioneer doctor," Gause often rode horseback as far as 20 miles to remote Kansas towns to treat patients. 2, 8

During his early tenure as hospital superintendent, Gause, in contrast to "the militant tendencies of some of the local hospital leaders," tried to establish a "moral treatment" hospital instead of a custodial care only facility. In the asylum's annual report for the first year, Dr. Gause states his views on mental illness, "Insanity is a disease of the brain affecting one or more mental faculties,; and is no longer regarded as the extinction of the mind, as hopeless and incurable, but arising from physical causes which disable the brain for a time from correct exercise of those functions through which the mind is represented, and by proper treatment can be removed."2, 8

With the exception of a year off for rest, Dr. Gause and his wife served as superintendent and matron of the asylum from 1866 to 1871.

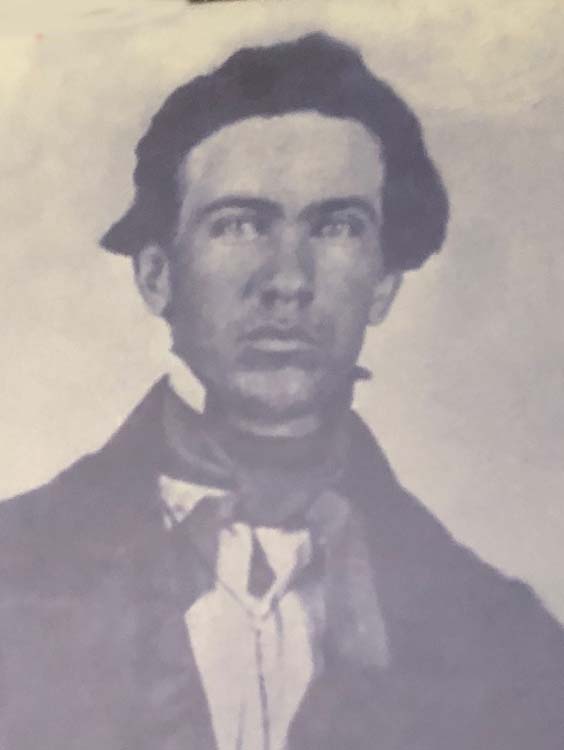

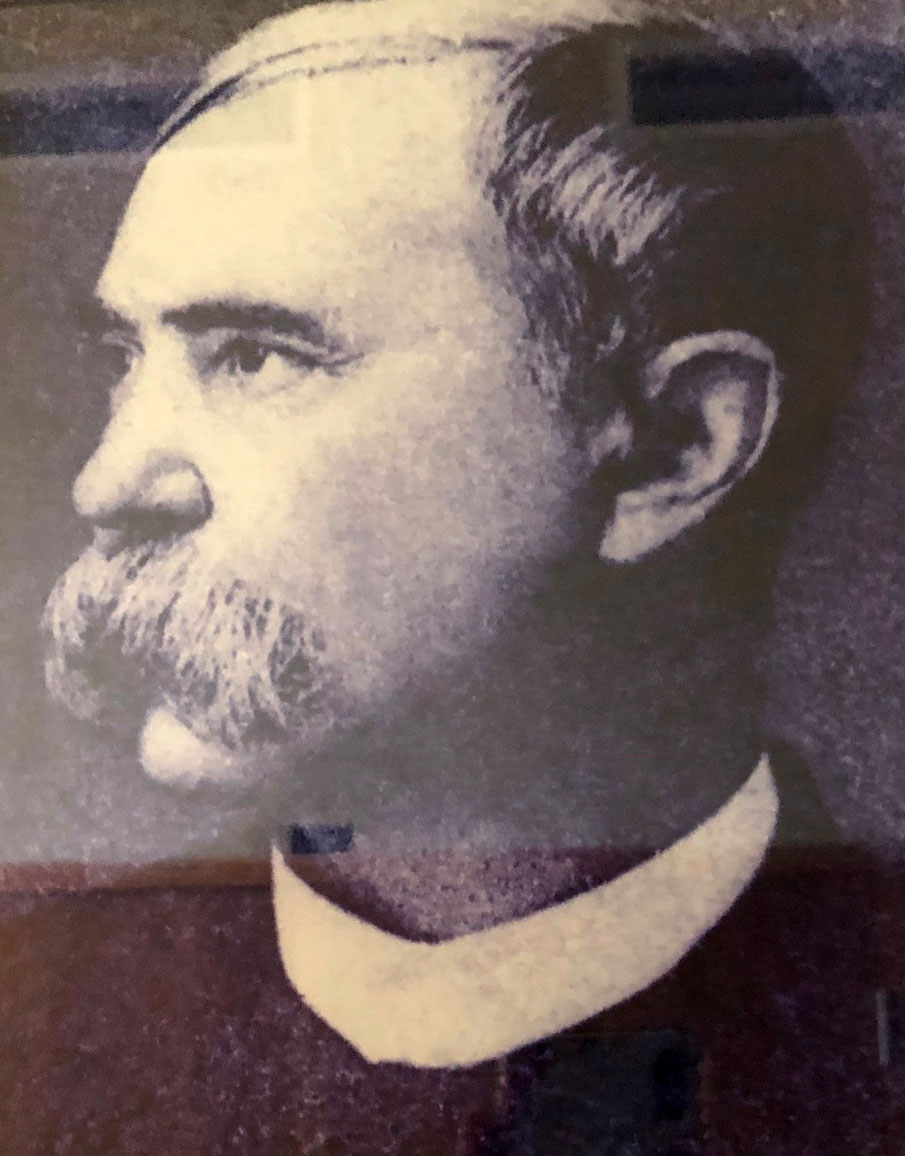

An early photo of the first supertindentent of the Kansas State

Insane Asylum, Dr. Charles Gause, located in the Osawatomie

State Hospital Administration Building display area.

Photo by P Marlin 2019

An early photo of the first supertindentent of the Kansas State

Insane Asylum, Dr. Charles Gause, located in the Osawatomie

State Hospital Administration Building display area.

Photo by P Marlin 2019

A later photo of the first supertindentent of the Kansas State Insane Asylum,

Dr. Charles Gause. This photo is located at the Osawatomie

History Museum in Osawatomie. Photo by P Marlin

A later photo of the first supertindentent of the Kansas State Insane Asylum,

Dr. Charles Gause. This photo is located at the Osawatomie

History Museum in Osawatomie. Photo by P Marlin

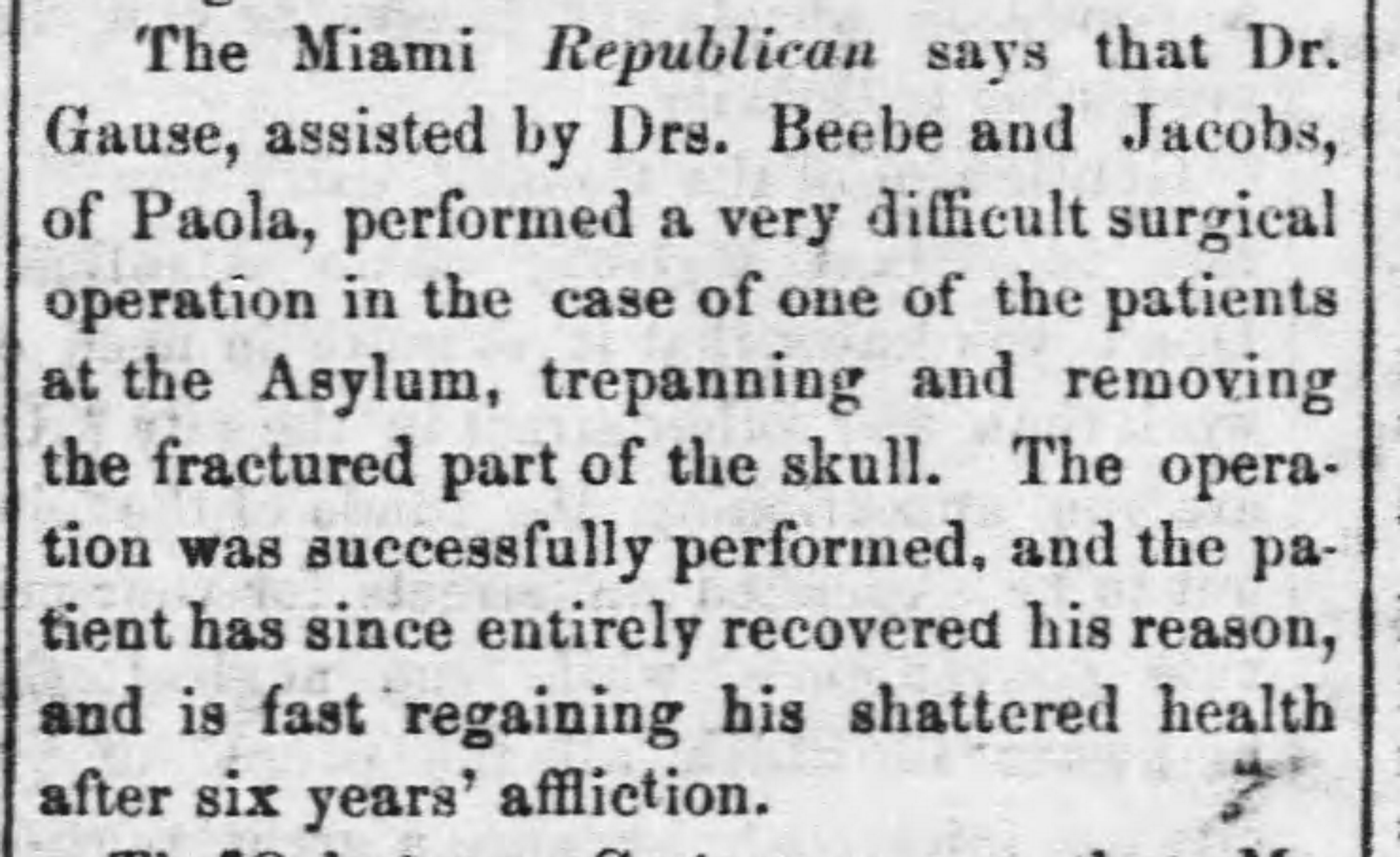

The Weekly Atchison Champion of July 2, 1870, describes a

successfull operation by Dr. Gause.

The Weekly Atchison Champion of July 2, 1870, describes a

successfull operation by Dr. Gause.

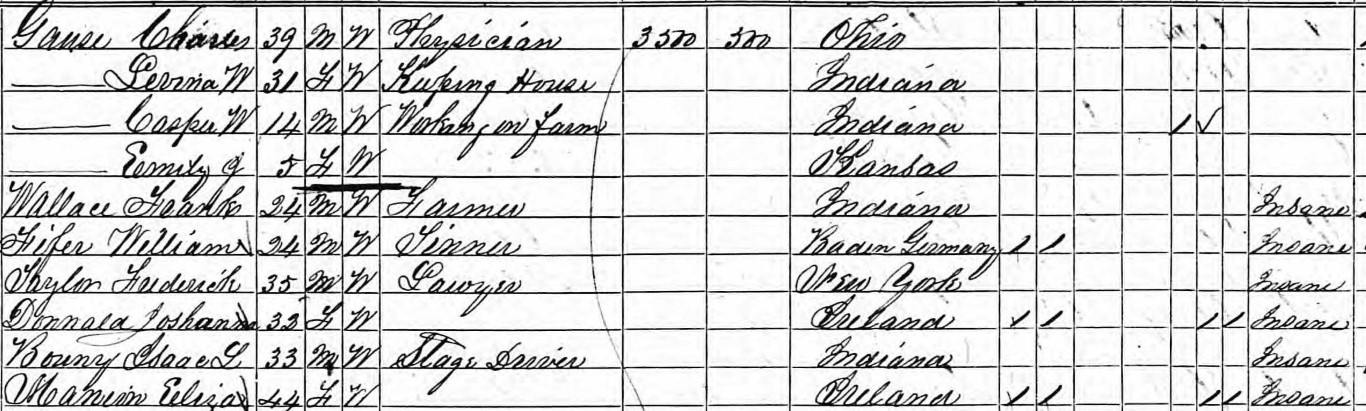

The first census taken at the Kansas State Insane Asylum in

1870. This census lists Dr. Charles Gause, his wife Levina,

and his children, Casper and Emily. It also lists the 'insane'

patients at the asylum.

The first census taken at the Kansas State Insane Asylum in

1870. This census lists Dr. Charles Gause, his wife Levina,

and his children, Casper and Emily. It also lists the 'insane'

patients at the asylum.

For several deacdes the day was opened and closed by the ringing of a large, 250-pound bell that Dr. Gause donated to the hospital in 1868. "The bell shall be rung at sun-down, when all the patients shall be locked in the ward halls. All employees must rise at the ringing of the morning bell and at once commence work; and they must retire at none-o'clock." 2

Two additional wards were added in 1868, however, overcrowding at the asylum soon became an issue. The need to admit numerous mentally ill patients placed pressure on the superintendent and the facilities of the hospital. Dr. Charles Gause, superintendent, reported these problems in the fourth annual report of the asylum:

"Among the causes of insanity we find spiritualism charged with two of the inmates; disappointed love with two; religious excitement with one; novel reading with one; failure in business with two and domestic trouble with two. The present building is too small, as it has only two small wards with nine rooms devoted to the use of inmates of both sexes." 4

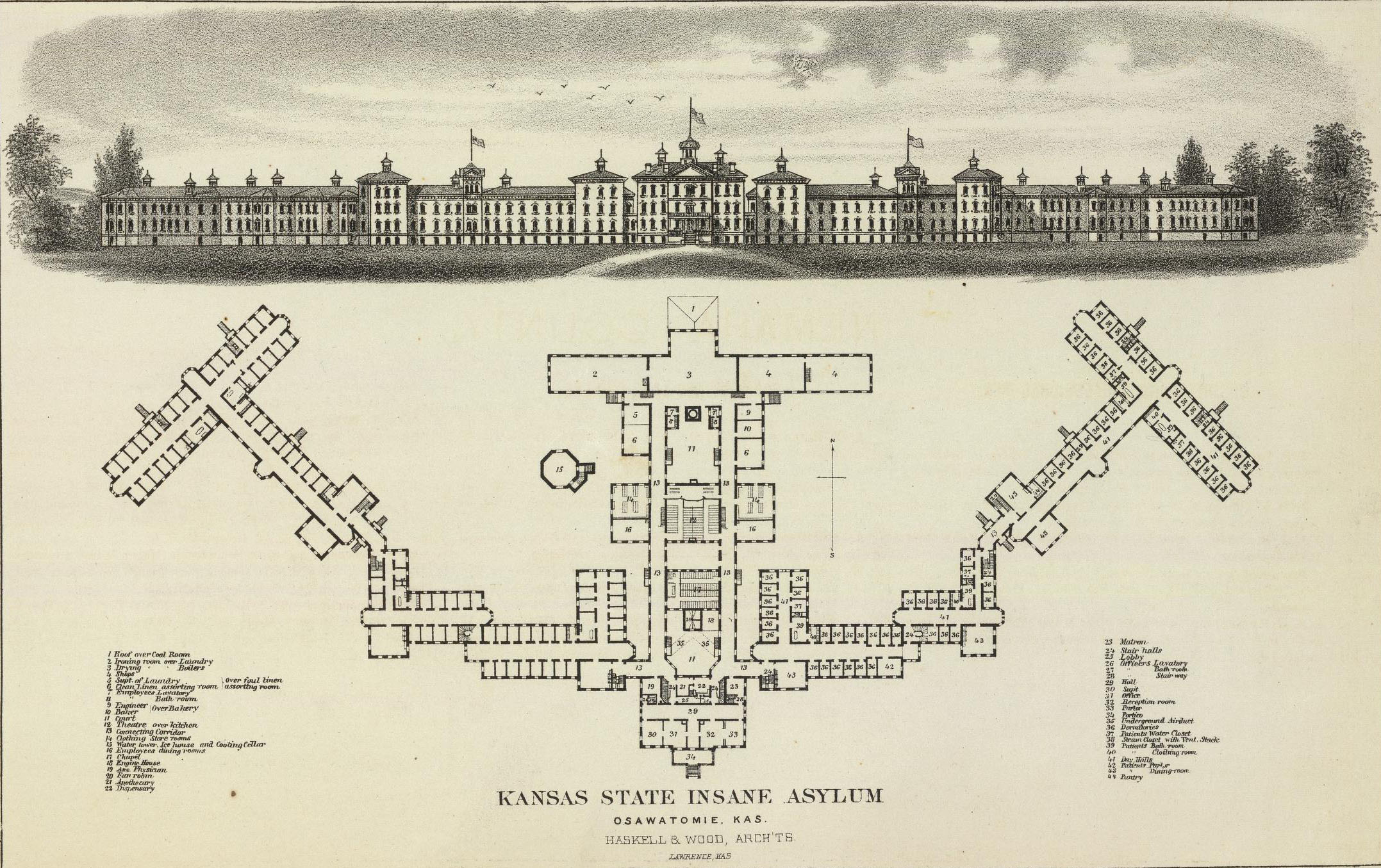

In 1868, the Kansas legislature appropriated funds for a permanent treatment structure to replace all of the existing structures on the asylum grounds. State architect J.G. Haskell presented plans drawn according to the recommended design by Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride of Pennsylvania. Dr. Thomas Kirkbride was a Quaker physician and Pennsylvania State Hospital superintendent "who developed a system of institutional management and a complete plan of architectural arrangement." 8 Kirkbride pioneered what would be known as the "Kirkbride Plan" to improve medical care for the insane as a standardization for buildings that housed the patients.

The center of the building had twin turrets for administrative offices with extended wings offset right and left for patients. The wings were placed so that fresh air could reach them from both sides.

The Kirkbride plan

Dave Rumsey Maps

The Kirkbride plan

Dave Rumsey Maps

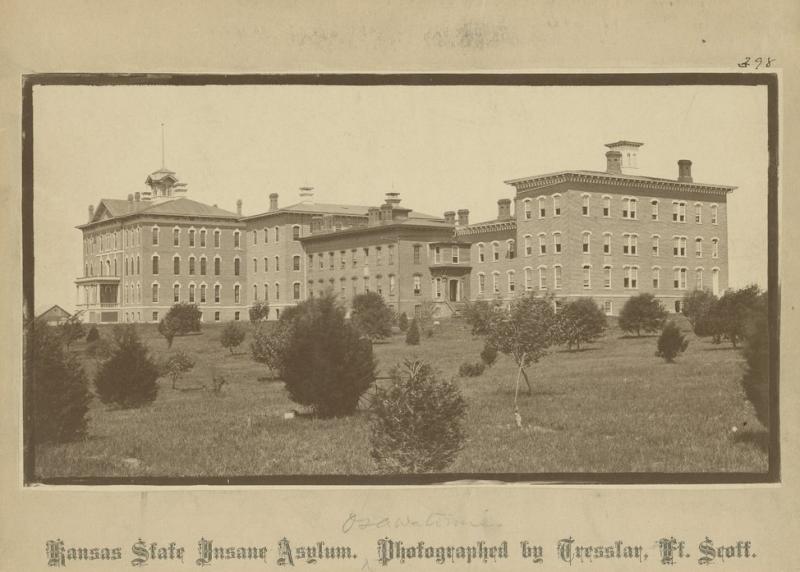

As the 1868 Kirkbride plan for new buildings progressed over the next 18 years, the need for additional patient space presented a continual problem for the asylum.

An excerpt from the The Weekly Commonwealth on January 6, 1876 states, "The second period embraced the erection of the brick building known as the east wing, which the observer will distinguish by the dark color of the brick of which it is built, and the dark trimmings which give it a somber appearance. This was considered a magnificent structure at the time. It was crowded as soon as opened. It admitted no division of the patients, except as to sex. 6

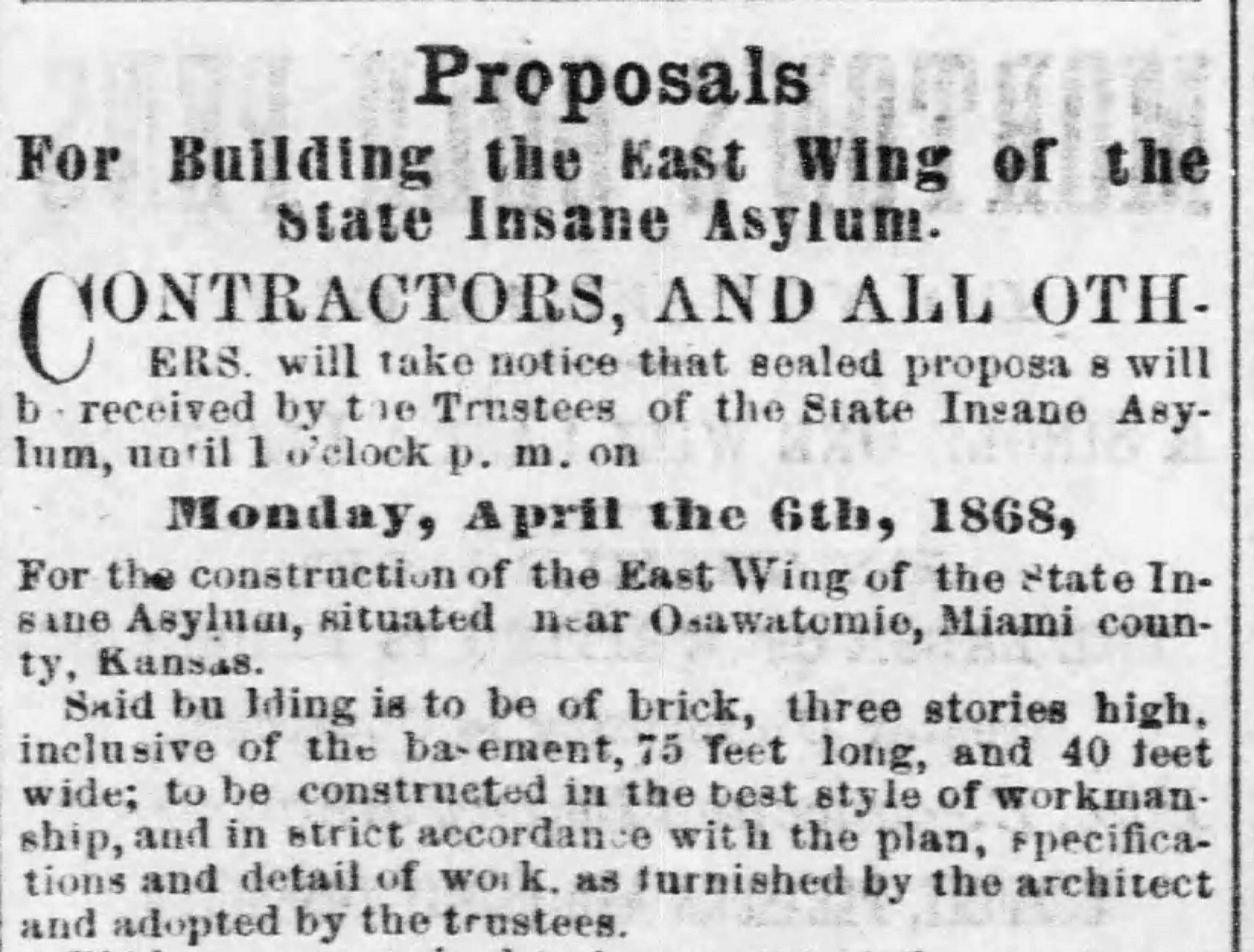

Notices were placed in local papers welcoming proposals from contractors for building the east wing of the State Insane Asylum. According to the 1868 Biennial Report, the new Asylum building was 40 x 75, three stories high, including a basement. When complete, the building "will be a very well planned and constructed building, and answer the purposes for which it is intended admirably. It is capable of accommodating some 30-40 patients." 7 However, the report also stated that the hospital had over 50 pending applications and that accommodations would soon be inadequate again.

Notice in the Daily Kansas Tribune March 26, 1868.

Notice in the Daily Kansas Tribune March 26, 1868.

Additional descriptions of the east wing are revealed in the asylum's 1868 annual report:

"The second and third stories are each twelve feet in height. The front of the second story is divided centrally by a hall, eight feet wide in which the stairway, on one side of which is the office and dispensary, and on the other side the parlors. Immediately in the rear of these and on the same floor is the first ward. The third story is divided substantially, into halls and wards, with family room, on one side of the front hall and bedrooms on the other. One room in each ward is for the "ward attendants" and one room in each for privy and bathroom, leaving eight rooms in each ward for patients. The comfort of all concerned was greatly promoted but the crowding was still too great as is evidenced by the fact that two patients occupy the same small room and at night the wards are filled with cots to accommodate sleepers." 72

The east wing.

The east wing.

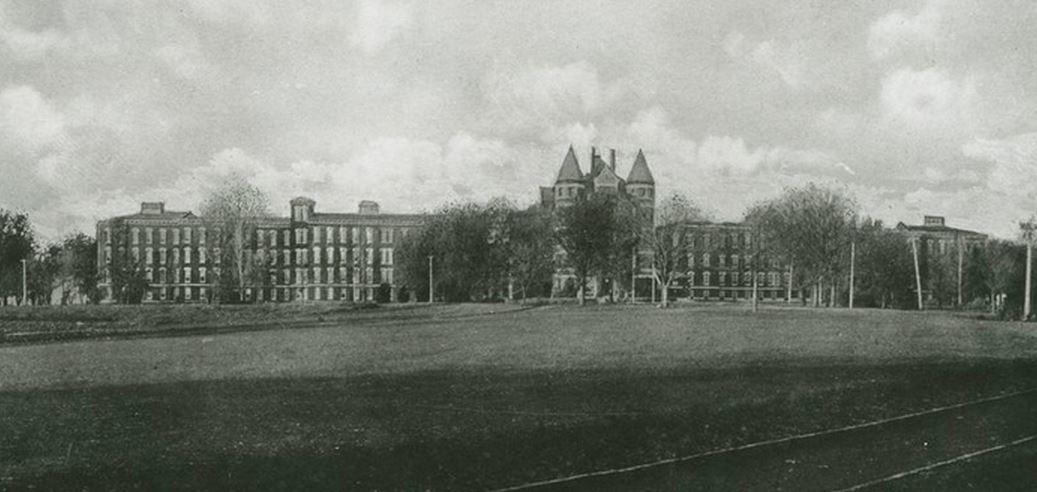

An excerpt from the The Weekly Commonwealth on January 6, 1876 states, The fourth period is the "age in which we live." The erection of a "central building" was provided for by the last legislature. 6

The main building, often referred to as "Old Main" was a five-story administration building. This building consisted of forty rooms, a chapel which sat 600 people, a stage and dressing-rooms, dormitories for the superintendents' stewards, physicians, clerks, matrons and supervisor's offices. In addition, dormitories were available for the employees who worked in the laundry, kitchen, sewing rooms, and shops.

The main (center) administration building "Old Main" with turrets and east

and west wings on either side.

The main (center) administration building "Old Main" with turrets and east

and west wings on either side.

The main (center) administration building "Old Main" with turrets and east

and west wings on either side.

The main (center) administration building "Old Main" with turrets and east

and west wings on either side.

Construction on "Old Main" started in 1869 and took 18 years to complete. There were the occasional setbacks. A fire in 1880 destroyed most of "Old Main," however, the east and west wings were saved.

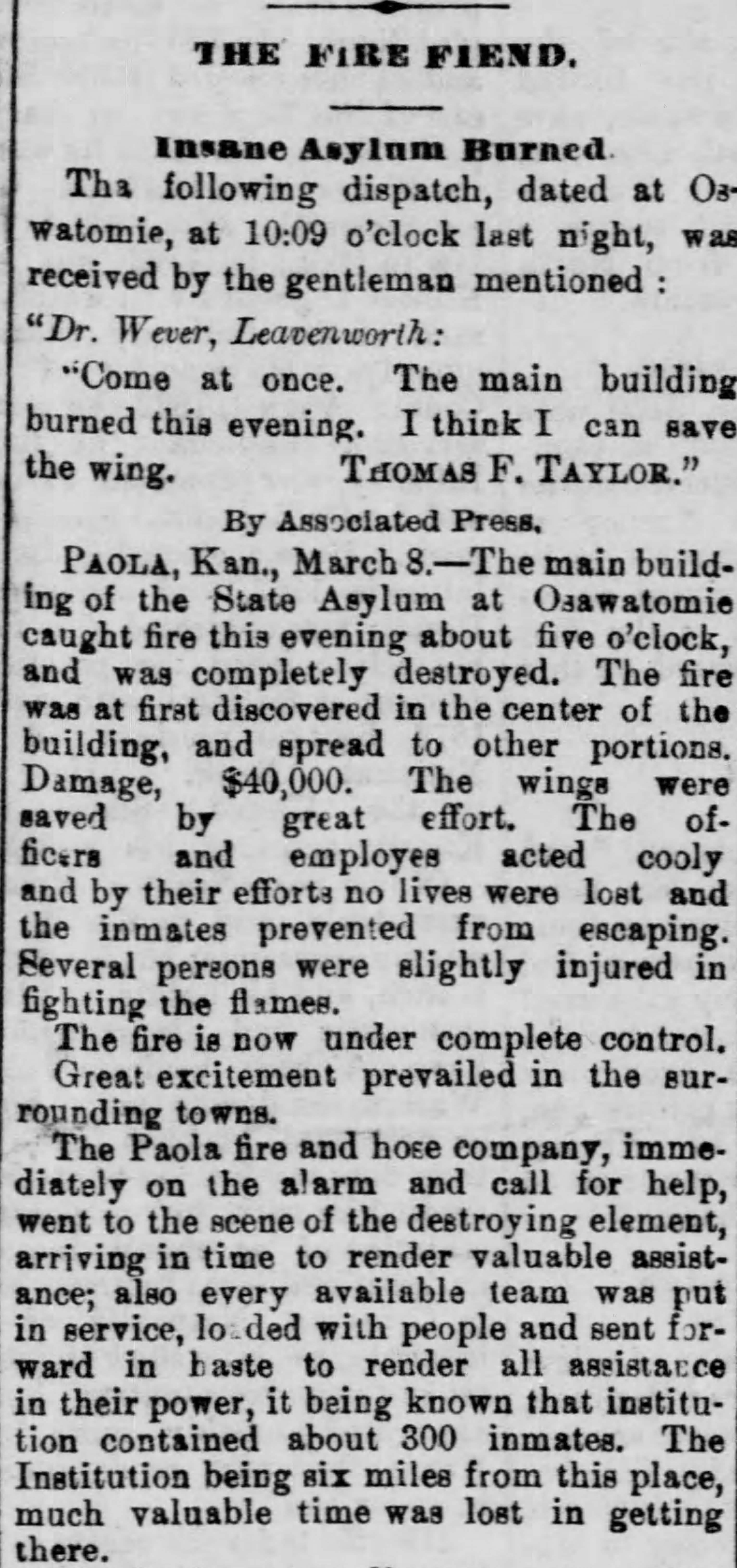

An article from The Leavenworth Times on March 9, 1880,

describes the fire.

An article from The Leavenworth Times on March 9, 1880,

describes the fire.

A description of "Old Main" under construction. An excerpt from the The Weekly Commonwealth on January 6, 1876 states,

"The asylum as seen on a winter's day, across the brown and serene prairie, has a lonesome look, although it is situated in the midst of a fairly settled farming country. It stands on the crest of a ridge overlooking the Marias des Cygne, beyond which, a mile or so away are seen the white houses of Osawatomie. The building as it now stands, is a rather imposing looking affair when seen at a little distance, but when close at hand reveals the fact that it has been constructed at different times, although the attempt has been made to make the different constructions harmonize with each other, and with a general plan. The large central building is not yet completed, and is more or less marred in appearance by scaffolding and the earth, rubbish and material which accumulates around buildings in course of construction. Near at hand is a two story white frame house, getting into the "serene and yellow leaf," looking like what is was originally, a farm house, this was the original Kansas insane asylum." 6

The years 1892 and 1895 saw the addition of two detached buildings, the Knapp and Adair buildings. The Knapp building, named for former superintendent Abram H. Knapp, was completed in 1892 and housed 300 "chronic" or "incurable" male patients (the Knapp building was closed in the 1960’s).

The Knapp Building

which no longer exists.

The Knapp Building

which no longer exists.

Abram H. Knapp served as superintendent from 1873-1877 and again from 1878-1892. His tenure as superintendent was considered stormy and tempestuous. Knapp was a controversial figure from the start, two months after he assumed authority as superintendent, a number of asylum employees protested against the "new and more rigid form of administration" by marching off in what was considered a "mutiny." 8

With the steady increase in the number of patients, there was a prevailing need to economize patient care. Knapp traveled east to assess the best institutional practices at some of the best asylums. Noting that some asylums were in a state of decline, he tried to establish procedures that "were not necessarily therapeutic or beneficial but represented "standard practice." Dr. Knapp came to believe in the importance of a militarylike discipline for the promotion of efficiency and economy." 2

A photo of superindendent Abram H. Knapp of the Kansas State

Insane Asylum located in the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration

Building display area. Photo by P Marlin 2019

A photo of superindendent Abram H. Knapp of the Kansas State

Insane Asylum located in the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration

Building display area. Photo by P Marlin 2019

In the employee manual for the asylum, Knapp expressed his philosophy of service, "No persons should engage in the Asylum service who are not willing to all their time and talent to the discharge of their duties. It is to be distinctly understood that the Asylum for the whole time of all employees, and that they will not be permitted to leave the premises of their duties, nor engage in work of their own in working hours, without express permission from the Superintendent." 2

In 1883 the Knapp administration was accused of living in “gentlemanly luxury.” There was criticism of a race track at the asylum that was said to have been maintained by patient labor. Knapp, as well as another doctor at the asylum, bred fine horses. Training and breeding of these horse, and potentially other animals, was under Knapp, Smith & Co and may have negatively affected the asylum as indicated in the poem below.

I'd never tell the news of Knapp, Of Knapp, M.D., the Asylum Chap

Who robbed the crazy of their milk, To feed his dogs, as fine as silk;

Who robbed the crazy of their food, Because his pups were pups of blood;

Who stole the blankets from the sick, To keep his horses warm and sleek.

There is few like him this of -well, The tale of Knapp I'll never tell. -Doggrel 2

It was generally felt that the interaction between staff and patients deteriorated during Knapp's administration and previous attempts at "moral treatment" had disintegrated. Though Knapp was a strict disciplinarian, he was also called considerate and humane, dealing tenderly with the infirmities of the insane. The years of controversy took their toll on Knapp, "Through the years he was proclaimed both a saint and a demon, and the cloud created by the controversy is so murky that the determination of which designation might have been more accurate, is difficult. In 1890l he resigned and returned to Ottawa. The sounds were too severe or the peace of retirement too foreign, for Dr. Knapp died a few months later." 8

In 1895 the Adair building was added to accommodate 300 of the "chronic" or "incurable" female patients. This new building was named for Reverend Samuel L. Adair, a key figure in the asylum's early establishment (original 1895 Adair building was closed in 1963 and a new Adair complex of multiple buildings was opened in 1963).

The original Adair building

which no longer exists.

The original Adair building

which no longer exists.

In 1868 when the state of Kansas decided to establish a permanent structure, Samuel Adair and his son Charles contributed or sold nearly 50 acres of land to help the state establish the asylum. Reverend Samuel L. Adair was a congregational minister who established the first church in the town of Osawatomie. He also served as Secretary on the asylum's board of trustees and was chaplain at the asylum.

An opponent of slavery, Adair was married to the abolitionist John Brown's half-sister Florella Brown. It was at Adair's persuasion that abolitionist John Brown and his sons moved to Kansas ushering in the Bleeding Kansas era. The Adair home, a small cabin in Osawatomie, was a station on the Underground Railroad and used as John Brown's headquarters during the uprising.

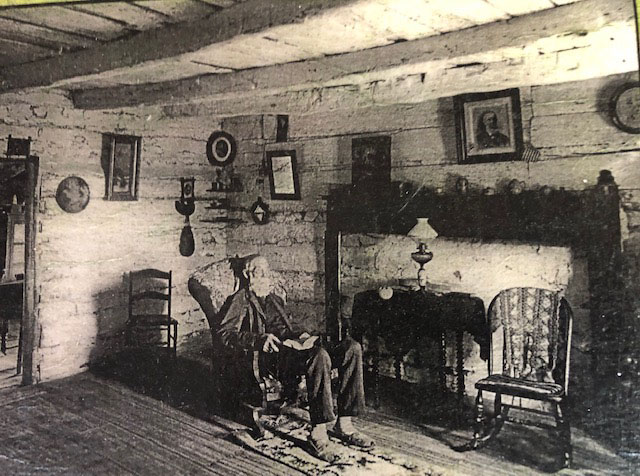

An 1894 photo of

Samuel Adair in his cabin. This cabin was also used by John Brown

during his abolitionist activities. The original cabin can be

viewed at the Adair Cabin State Historic Site in Osawatomie, Kansas.

Photo by P Marlin

An 1894 photo of

Samuel Adair in his cabin. This cabin was also used by John Brown

during his abolitionist activities. The original cabin can be

viewed at the Adair Cabin State Historic Site in Osawatomie, Kansas.

Photo by P Marlin

The original Samuel Adair at the Adair Cabin State Historic Site in

Osawatomie, Kansas. Photo by P Marlin 2019

The original Samuel Adair at the Adair Cabin State Historic Site in

Osawatomie, Kansas. Photo by P Marlin 2019

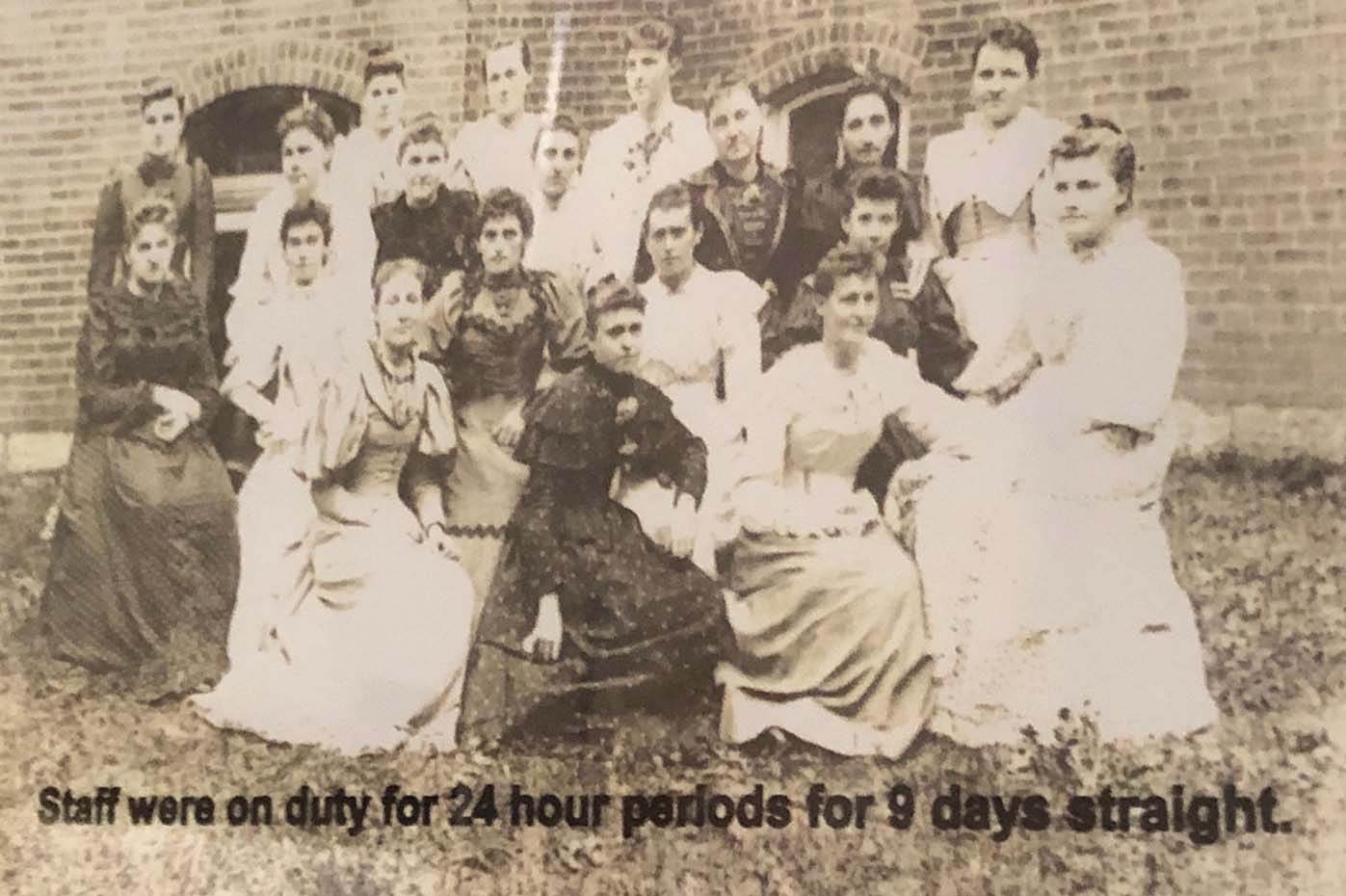

In the early years asylum attendants were not trained or properly

prepared to deal with patients. These workers were often faced

with “awesome responsibility, physical dangers, and an assortment of

other adversities.” Typically, attendants were awake before the patients

in the morning, and would not retire until the patients were locked

in their rooms in the evening. Night watch attendants were often

responsible for hundreds of patients. One attendant

could have up to 200 patients under his watch. 2

An article from the The Topeka Daily Capitol

on September 12, 1888, provides perspective on the environment.

The writer noted that the “asylum patients'

attendants, both male and female, were quite young.

At this time, the attendants were only getting one day off for

every nineteen days of work. After interviewing one employee about

the work load, the writer noted that the work load was "wearing on

her nerves." One attendant described the working conditions under Dr. Knapp's

administration. "The rules are more strict under Dr. Knapp's

administration than they used to be under other superintendents.

The former superintendents thought that the attendents could not

stand the foul air in the wards too long, but Dr. Knapp put them

on double time. You may look at the attendants in the wards now,

and see how they look after being confined in the wards so long.

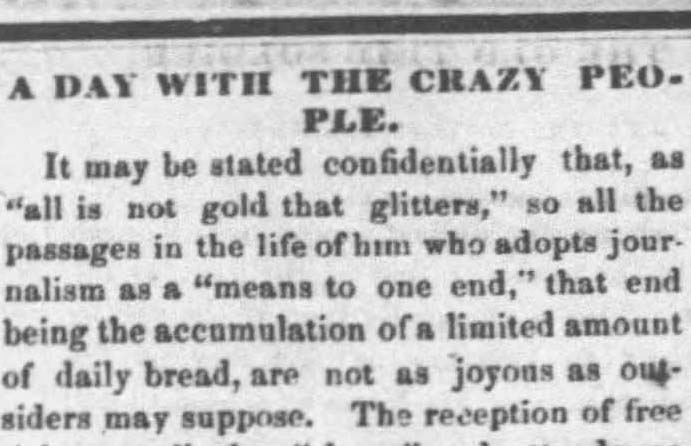

They have to stay on from 5 A.M. to 9 P.M." 2 The writer of The Weekly Commonwealth article of 1876, shares

the story of his visit to the Asylum with perspectives on the patient's care and

facilities. "Inside at last. We were first ushered into a very small room, made

still smaller by being partially divided by a partition separating

it from a sort of closet used as a dispensary. The walls were

adorned with stuffed snakes, which looked so lifelike that a

gentleman of convivial habits being suddenly ushered into the

apartment might be led to believe that he had "got 'em" and

was really condemned to stop awhile in the institution." "Under lock and key. An institution for the insane is

generally called an asylum, primarily a place of refuge, a final

home for the insane. But every asylum is a sort of prison.

There are gratings at the windows, and a prison-like aspect prevails.

So when a visitor goes into the wards the door shuts behind him

with a heavy clang, which every person must have felt, rather

than heard, when ushered for the first time into a prison cell." "Overwhelming sadness. In the one hundred and

three patients to be seen at Osawatomie not one has a bright eye,

the rosy cheek, the elastic step of youth. They are all sick

people "It is explain," said Dr. Knapp [superintendent], "in the words overworked

and underfed." Hard work and hard fare are the recruiting agents

for the army of the insane." "With the wild men. In what are called the 'wild

wards" are confined the most violent patients, the class associated

in our minds with "Bedlam." These wards are not, however, a scene

of continual noise and violence, the moods of patients greatly

varying from day to day. In a moment a patient may change from

perfect quietude to screaming violence." "The mad women. The grotesque fancies of insane

men sometimes provoke a smile, but the sights and sounds of the ward

of the "wild women" are simply horrible without a redeeming feature.

Such hopeless faces, such blood curdling sounds, such extremity

of mental and physical suffering are hard and witnessed nowhere

else." The writer continues to expound upon building additional facilities,

such as a library and a chapel that would further benefit the asylum. "Dance of the demented. The upper floor of one

of the buildings is devoted to the purposes of an assembly room.

In it the religious exercises are held, and on three evenings a week

dances are given for the benefit of the patients. The musicians,

all employees in the asylum, had taken their places when

we entered. The prompter said, "Take your places for a quadrille,"

the orchestra began. Gentleman employees took the floor with lady

patients, and vice versa. Among the dancers we observed Mrs. Knapp

and Miss Knapp, the wife and daughter of the Superintendent." "The treatment of the insane in our asylum seems

as near perfect as the facilities will admit. The writer

has several times visited the Kansas Penitentiary and has been

afforded every facility for examining its apartments by

the very competent gentleman at the head of the institution.

He has not hesitation in saying that he convict in Kansas is better

provided for than the insane person. There is a good library in

the prison, there is nothing approaching that in the insane asylum.

The chapel in the prison is one of the finest in the State. There

is nothing like it at Osawatomie. The cooking arrangements at

the penitentiary are better than those at the asylum." An 1888 asylum visit provides another perspective of the asylum

environment as shared in an article from The Topeka Daily Capitol

September 12, 1888. "A beautiful scene - and the asylum is a grand institution.

The building is of brick, four stories high, and has the capacity

of accommodating 500 patients - and its capacity at present

is taxed to its utmost limits." "And just here let me remark, that while visiting the

wards, even "the disturbed" ward, where the violent cases are

confined, I observed a certain amount of method in their madness.

All seem to appreciate the fact that they are under control.

Without guard or case, what harmful creatures the least vicious

are known to have become. Here, watched, cared, for, they are

harmless. " "And, whisky, according to Dr. Knapp [superintendent] it the

cause of the lunacy of the great majority of patients. "The

opium habit" has fewer victims than might be supposed. As pitiable

as the sights may seem in the men's wards, it becomes double so when

the 225 female patients are seen. Poor women." Dr. Knapp, Superintendent, describes how the women patients

are mostly "Farmers' wives and daughters. Hard work and

child-bearing. A young couple, ignorant of every physical

relation, marry, they settle upon a farm, go into debt

to get a roof over their heads, and both strive and work for a

living. The man works, and so does the woman, just as hard

and often harder and longer hours, and ignorance makes her a

mother, a mother again - a child at her breast, a baby

who merely creeps and another who totter as it puts out its feet

for the first steps. Physically nature cannot stand such a strain,

and that succumbing, the mind fails." By 1900 the asylum had expanded from its original 170 acres in 1866-1868

to 720 acres. Additional buildings included the main administration building

which held offices, a chapel, dormitories for employees, east and went wings for

patients, shops, a boiler house, electric light and power plant, ice house,

bakery, laundry, barns, green houses, and a reservoir for water supply.

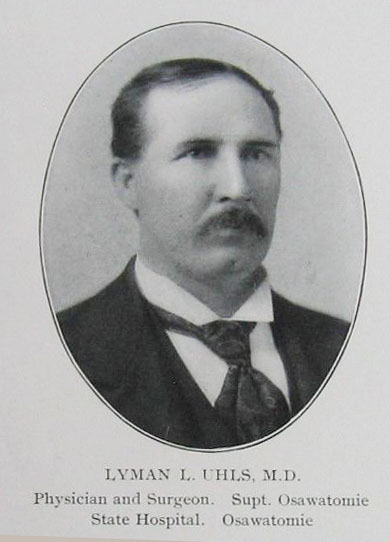

In 1899, Dr. Lyman Uhls, a prior assistant physician at hospital,

was appointed as Superintendent. He, along with his family, moved

into the Adair building. "Several basic changes occurred during Uhls' term, innovations

which prepared the way for actual treatment instead of custodial care

of patients. Dr. Uhls served less in the manner of general ruling

of a fortress and more as a leader. He removed the invisible walls

that had kept the various levels of staff member and employees

divided. He also took steps to meet the overpowering need for

educational programs for ward personnel to equip them to give

therapeutic service, rather than to serve as mere keepers

of patients. The superintendent also sensed the need for bringing the

community and the hospital back to a more harmonious relationship, and

during his administration the gulf between the institution and the

community was reduced. In 1901 the legislature took the step

that foretold the change that would come to the institution. The

Kansas State Insane Asylum was renamed Kansas State Hospital

at Osawatomie." 2 Further changes included an asylum baseball team with Superintendent

Lyman occasionally playing with the team. A two-year course of study for nurses,

the first offered in an institution west of the Mississippi. Equipment for

electrotherapeutics which became part of the patient's treatment plan,

and female nurses were allowed to care for male patients. In 1913 Dr. Uhls' resigned

his position as superintendent and established

a small mental hospital in Overland Park, Kansas. 2

During Uhls administration, the hospital came under investigation

for improper handling of patients who had died. Asylum staff

testimony described how the bodies were prepared at the hospital,

"The men being clad in a suit of underwear and wrapped tightly

in a winding sheet, the women being clad in a white burial robe

and wrapped in the winding sheet, which in every instance is pinned

tight to the body, which is placed in a zinc lined box in the morgue.

..some of the bodies were beginning to decompose when he received them,

and some were fly blown."

The investigation

and committee's findings were posted in local newspapers.

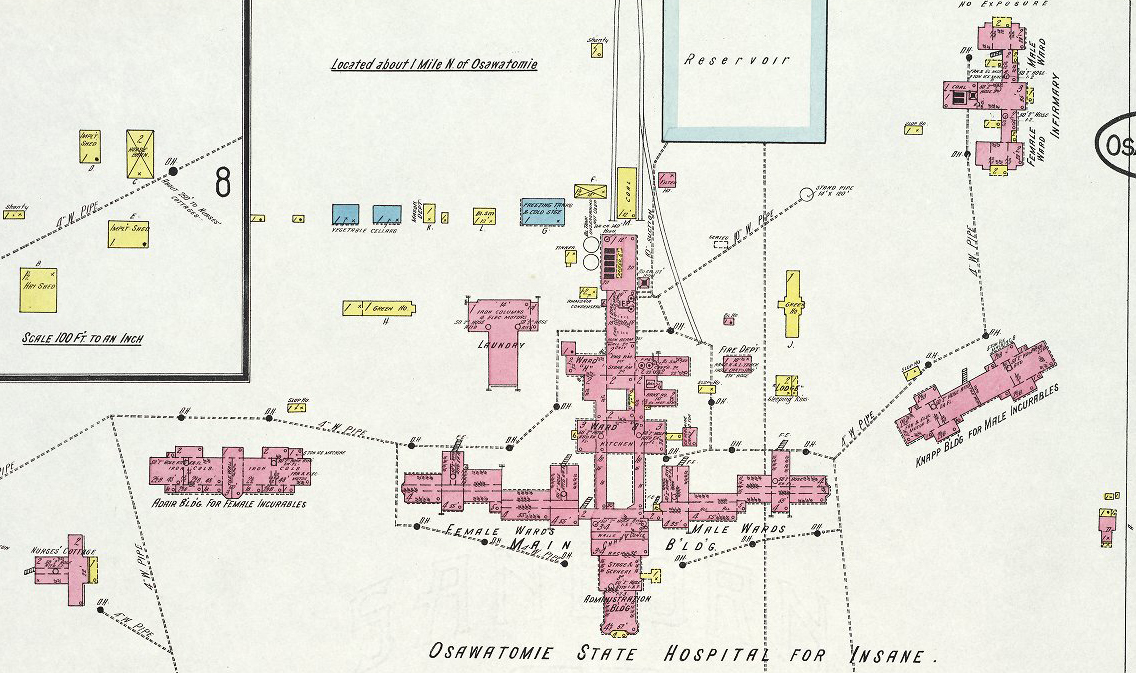

The following Sanborn Map shows the extent of the hospital's

buildings in 1913. Adelaide Amanda Richardson, my 3rd great-grandmother,

was born in Chautaqua county, New York, July 23, 1843.

She married Martin G. Hawley, my 3rd great-grandfather, in Michigan on July 27, 1862.

Martin and Adelaide had 5 sons, Walter, Jay, Eugene, Stephen and Ely.

In 1877, Martin and Adelaide moved their family to Anderson County,

Kansas traveling across the country in a covered wagon. It was

here that they established their homestead and raised

their boys. On March 28, 1906, at the age of 63, Adelaide was admitted to

the Osawatomie State Hospital by her husband. According to her

commitment papers, Adelaide had "disregard for personal

appearance and filthy habits of recurrent origin. Delusional

without a basis coupled with family history, and _____ unsanitary

environments." The papers also note that Adelaide's grandfather

hung himself and her mother had periods of derangement. Adelaide died at the hospital on June 24, 1906. In 1906, the fifteenth biennial report for the hospital

described the procedures followed when a patient was

admitted to the hospital. Adelaide's admittance was probably similar

to this. "First, the receiving physician examines all commitment papers,

and if found correct the patient is placed in charge of the supervisor.

He is taken to the ward selected by the ward physician; is then given

a bath and a suit of clean clothing. All important marks, scars or

deformities are recorded. A complete record of all articles of

clothing is made, as well as of money and articles of value on the

person of patient. All money is turned over to the clerk, who opens

an account with the patients. All watches, jewelry, etc., are taken

charge of by the ward physician, and after being marked, are placed in

the vault. The ward physician, the supervisor and the ward attendants

try to make the newly committed patient feel that he is among

friends. The attending physics puts him on medical treatment.

He is given plenty of plant, nourishing food, is kept cleanly

and comfortably clothed." 2 Source: Kansas Historical Society After the turn of the century, doctors still did not fully

understand what caused their patients' behavior, as evidenced by

what they documented as the source of their conditions. They listed

such things as religious excitement, sunstroke,

and reading novels as possible causes of mental illness. Additionally,

they believed that patients had lost all control over their morals,

and strict discipline was necessary to help the patient regain

self-control. The asylum provided the restraint a patient could not

supply himself. Confining the patient in a straitjacket was one way

to do this. Many doctors considered straitjackets to be a humane form of

treatment, far gentler than the chains patients encountered in prisons.

The restraint supposedly applied no pressure to the body or limbs and

did not cause skin abrasions. Moreover, straitjackets allowed some

freedom of movement. Unlike patients anchored to a chair or bed by

straps or cuffs, those in a straitjacket could walk. Some doctors

even recommended restrained individuals stroll outdoors, thereby

reaping the benefits of both control and fresh air. Considered humane by some, straitjackets were frequently misused.

Over time, asylums filled with patients and lacked adequate staff to

provide proper care. The attendants generally were not trained to work

with the mentally ill. Some feared the patients and resorted to

restraints to maintain order and calm. Patients might remain in restraints for days. Such was the case at the Osawatomie State Hospital. The facility

had beds for 12 patients when it opened. By the end of the next year

it housed 22 with applications for 50 more. In 1945, the ratio of

patients to physicians was 854 to one. As a result of such conditions,

restraints were used longer at Osawatomie than in Kansas' other mental

health facilities. The documented use of straitjackets continued until

at least 1956. Around 1950, Charles H. Graham, a reporter with the Kansas City Star,

wrote a series of articles on the conditions at Kansas' state hospitals.

At Osawatomie he found that force was commonly used to restrain male

patients, while females wore straitjackets and wrist cuffs. One attendant

reported that of the 70 patients on the ward, half might be in

straitjackets at any given time. Graham saw no apparent abuse in the

women's ward, but described the scene as bedlam: "These women were doing the best they could in a building that is

utterly unfit for the care of mental patients, or any other kind. . . .

There is no place to which any patient can retire to escape momentarily

the Bedlamic scene, and as a result, some of them 'blow up.' That brings

on the restraints." Graham found it interesting that Osawatomie continued

to use restraints while Larned State Hospital, a facility for the criminally

insane in western Kansas, had abandoned them by 1948. Osawatomie was eventually able to phase out the use of restraints

through increasing staff and improving facilities. Advances in

psychology, including the development of tranquilizing

drugs, made the devices unnecessary. Attendants were still leery

of removing the restraints, though. According to one, "They were

convinced that the patients would kill us. We couldn't

get a mental image of any other way than repression." A new infirmary building was added in 1902. The appropriation

for the new building was $45,000, however, the cost to build it surpassed

that amount. Hospital employees and patients completed

much of the work. The superintendent at the time, Dr. Lyman Uhls, provided

a summary in his 1902 biennial report. "We did all the excuating,

quarried all the stone for the foundation, and put them on the ground.

With only a little extra help, we set the boilers and installed the

heating plant. The cement floors in the basement and on porches

are to be put in by us." 2 The Asylum bridge was built in 1905 and was abandoned in the

1970's. In the early years, this bridge was part of the only road

that traveled north from Osawatomie to the Asylum and points north.

Today the road from the bridge still travels along an original

brick road which provides access to the east entrance to the hospital. The Osawatomie State Hospital Burial Grounds are located north

the hospital. It is a small cemetery consisting of

346 markers identifying people, mostly patients, who had no families

that would claim them. Miami County Historical Museum in Paola documents:

An excerpt from The Salina Journal on May 29, 2000, describes

the present state of the cemetery. "Records show that from 1874 to 1928, the

unclaimed bodies of patients were buried in a different area

on the northwest corner of the hospital grounds. Before 1874,

the dead were buried elsewhere on the grounds, but where that is

remains a mystery. In 1928, the headstones from the old cemetery were moved to

the current memorial site, but the bodies were left behind.

In the 1960's, the hospital constructed new Adair buildings on the

old cemetery. The buildings were on slab foundation so as to not

disturb the dead. So the plot one sees today east of the hospital mixes

memorial headstones from the earlier burial site with the actual

graves of those buried from 1928-1960. Hospital records that identify

those memorialized in the 346 plots are sealed." 9 In 1971 the original Kirkbride building east and west wings were demolished.

In October 2002, the "Old Main" was demolished. The area

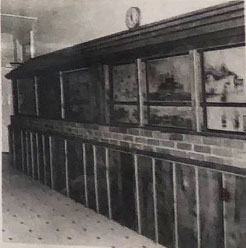

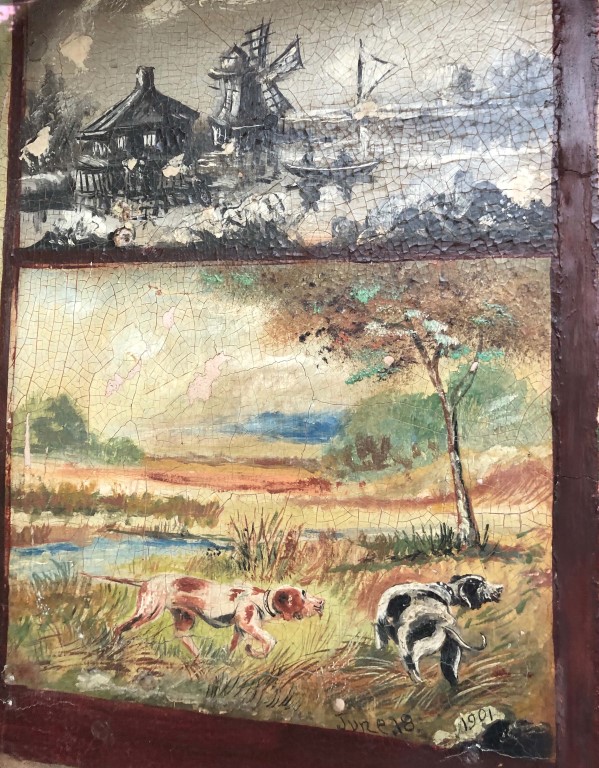

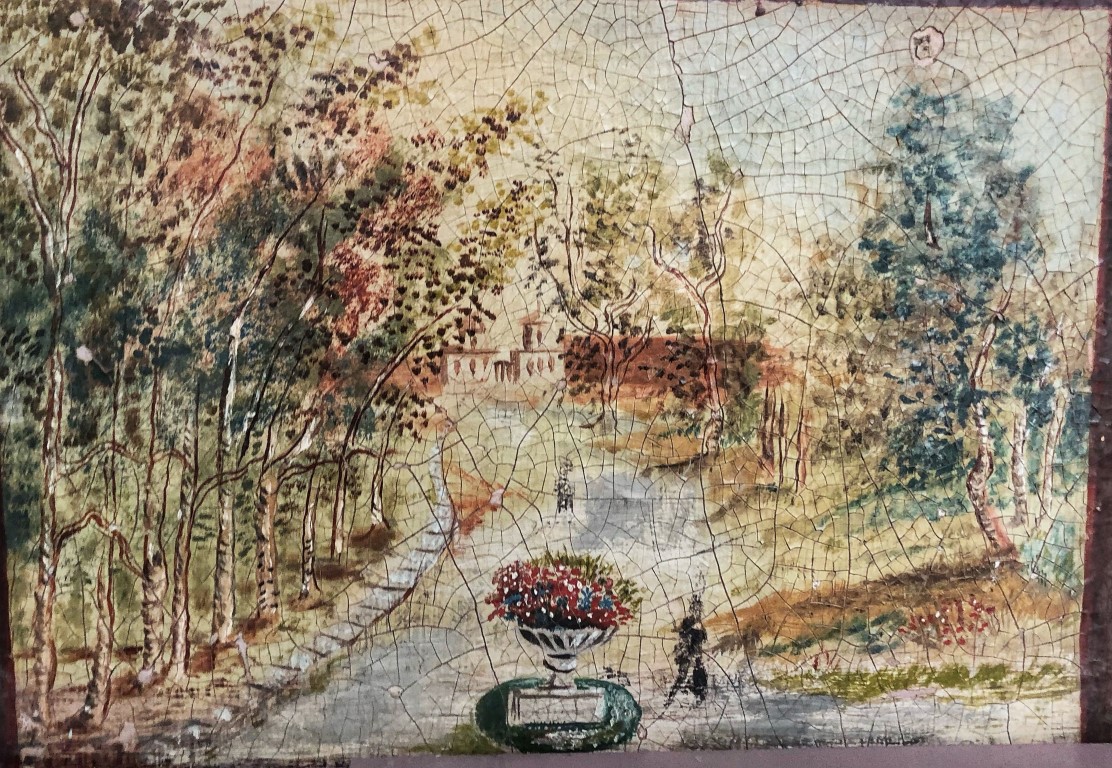

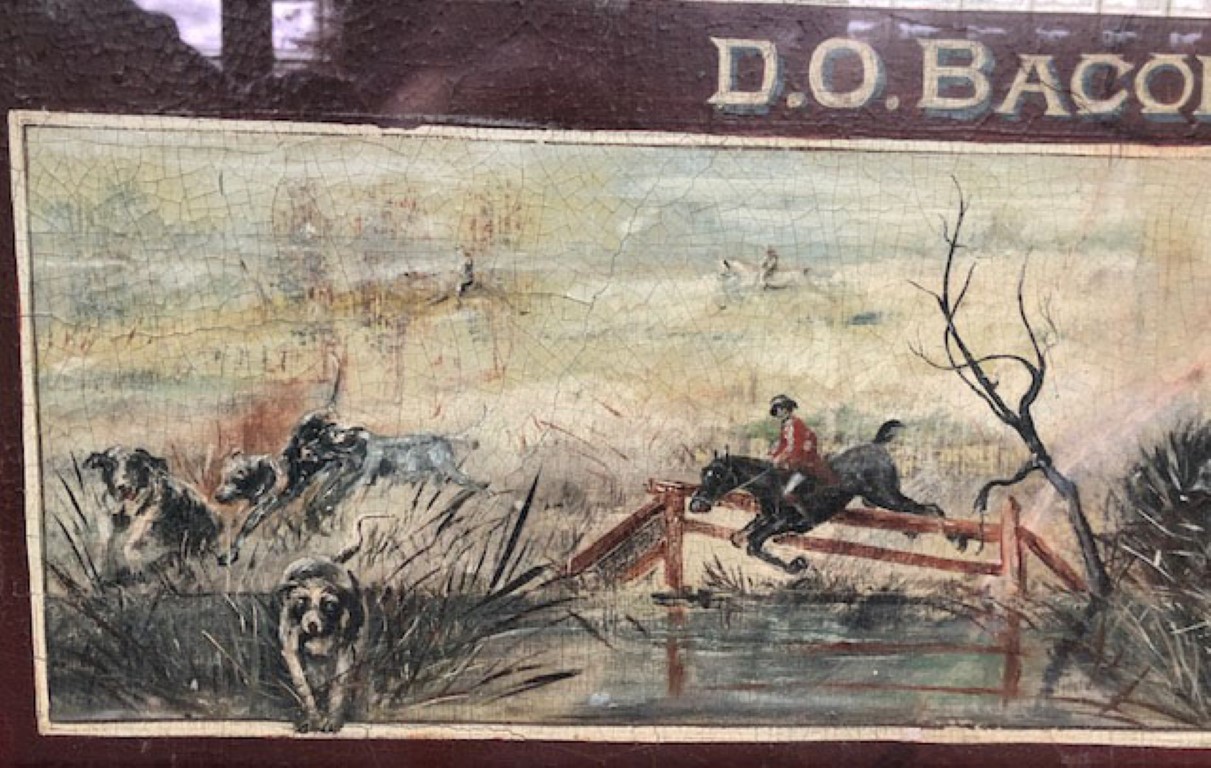

in front of the "Old Main" was known as the sunken garden. Today these murals are on display in the main administrative of

building of Osawatomie State Hospital. It was thought that the

murals would be destroyed when "Old Main" was torn down, however,

they were preserved by a process of drill holes and inserting long

bolts into the walls every 30 inches. Plywood was attached to the

mural to protect it and keep it in place, and then they were "sawed out"

of the wall. I was not an easy task, but the murals were preserved

Bacon was discharged as recovered on June 30, 1902.

1 Volume II of Kansas: a cyclopedia of state history 2 Gish, Lowell. 1972 Reform at Osawatomie State Hospital. 3

The Emporia News November 6, 1868. 4

Wyandotte Commercial Gazette May 10, 1869. 5 A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans, Volume 2 6 The Weekly Commonthwealth January 6, 1876. 7

Kansas State Insane Asylum At Osawatomie and Oswatomie State Hospital Biennial Reports 8 Gish, Lowell. 1966. The First 100 Years. Provided by the Miami County Kansas Historical Museum 9 The Salina Journal. City of Osawatomie forced to face its past. May 29, 2000. Special thanks to Jenny Cummings, staff member at Osawatomie State Hospital, Betty Berndorf at the Miami County Historical Museum in Paola, and

Ted Hunter at the Osawatomie History Museum in Osawatomie, for their assistance in the research for this blog. Please note: the photographs taken of the Osawatomie hospital were take in coordination with and approval

from hospital administration staff and security. Osawatomie is an active hospital with resident patients.

Hospital administration and security staff take very serious their job in protecting the privacy of

their patients and meeting related regulatory requirements. Kansas State Insane Asylum atendents. Photo taken by P Marlin

at the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration Building display.

Kansas State Insane Asylum atendents. Photo taken by P Marlin

at the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration Building display.  Kansas State Insane

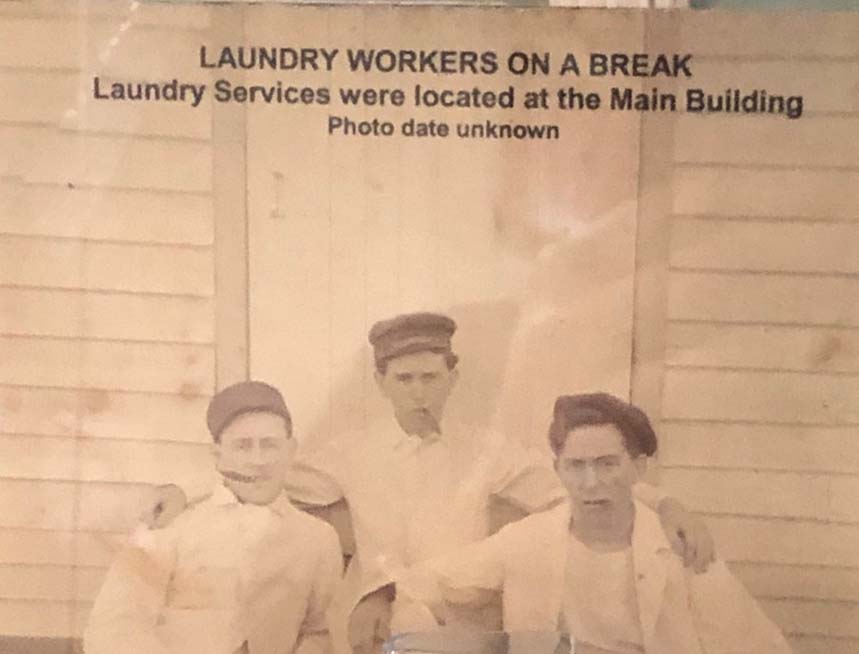

Asylum laundry staff. Photo taken by P Marlin

at the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration Building display.

Kansas State Insane

Asylum laundry staff. Photo taken by P Marlin

at the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration Building display.  Kansas State Insane

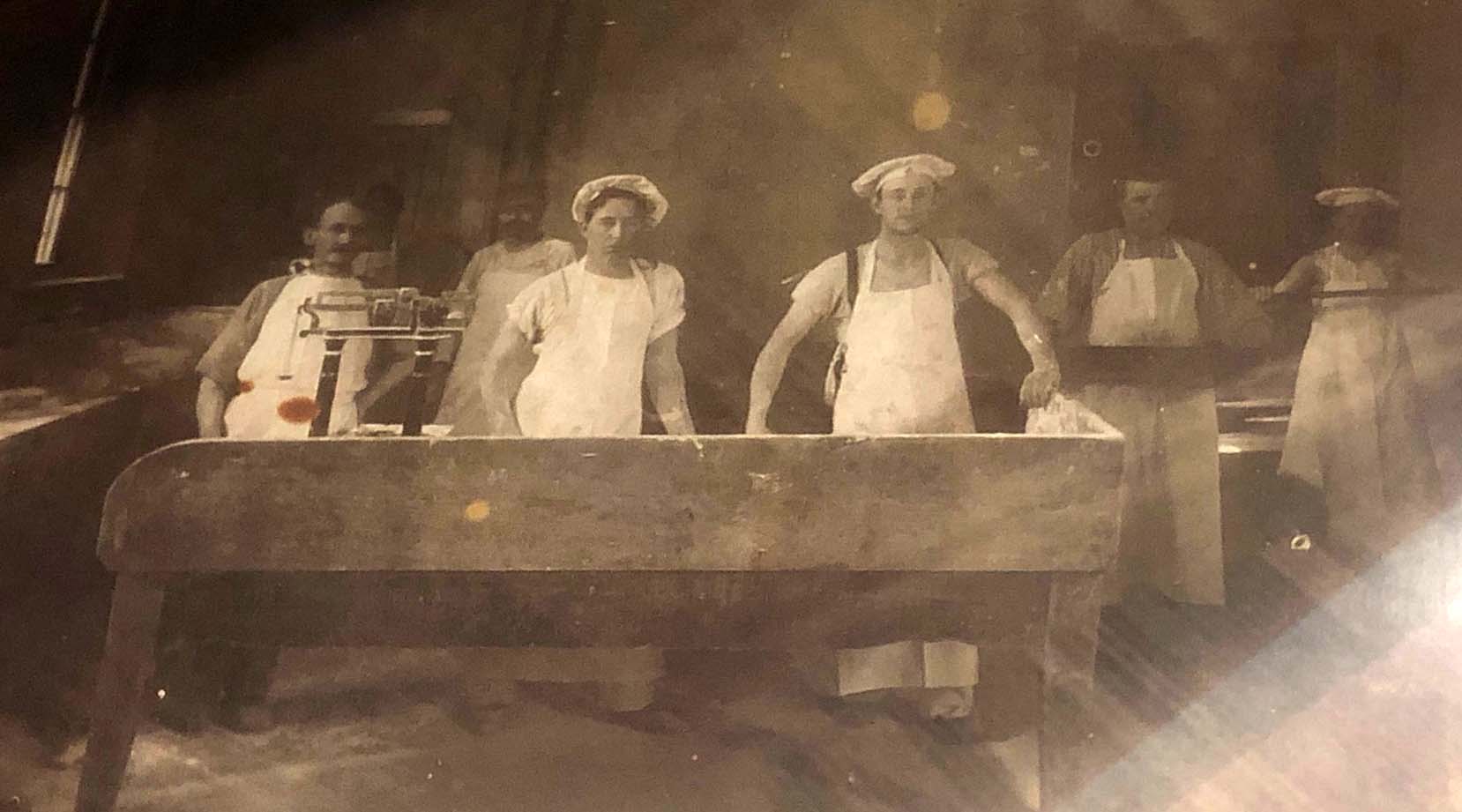

Asylum kitchen staff. Photo taken by P Marlin at the Osawatomie

Kansas History Museum.

Kansas State Insane

Asylum kitchen staff. Photo taken by P Marlin at the Osawatomie

Kansas History Museum. A Day with the Crazy People (1876)

An Asylum Visit (1888)

The Turn of the Century and Dr. Lyman Uhls (1899-1906)

Lyman Uhls.

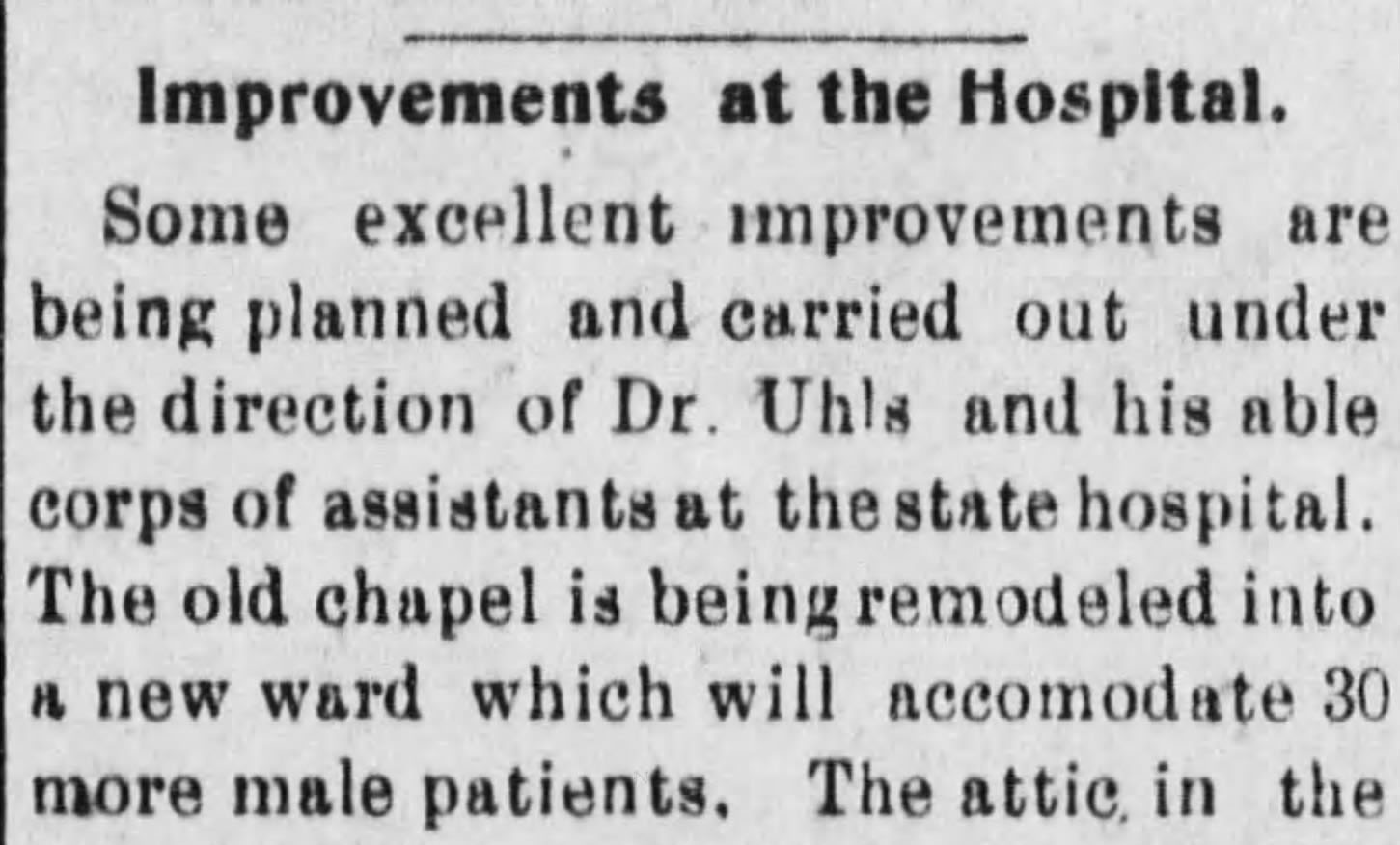

Lyman Uhls. The Osawatomie Graphic reports on "Improvements at the Hospital" on September 4, 1903.

The Osawatomie Graphic reports on "Improvements at the Hospital" on September 4, 1903. A 1913

Sanborn Map of Osawatomie State Hospital. A larger view of the

Sanborn Map shows the left wing of the main administration

building held the female wards with the male wards in the right wing.

The Adair building is to the left of the main administration

building wings, and held the "female incurables." The

Knapp building on the right held the "male incurables."

A 1913

Sanborn Map of Osawatomie State Hospital. A larger view of the

Sanborn Map shows the left wing of the main administration

building held the female wards with the male wards in the right wing.

The Adair building is to the left of the main administration

building wings, and held the "female incurables." The

Knapp building on the right held the "male incurables." Adelaide Amanda Hawley, Patient (1906)

Family photo with Adelaide in the chair to the left with her husband,

Martin Hawley, and sons.

Family photo with Adelaide in the chair to the left with her husband,

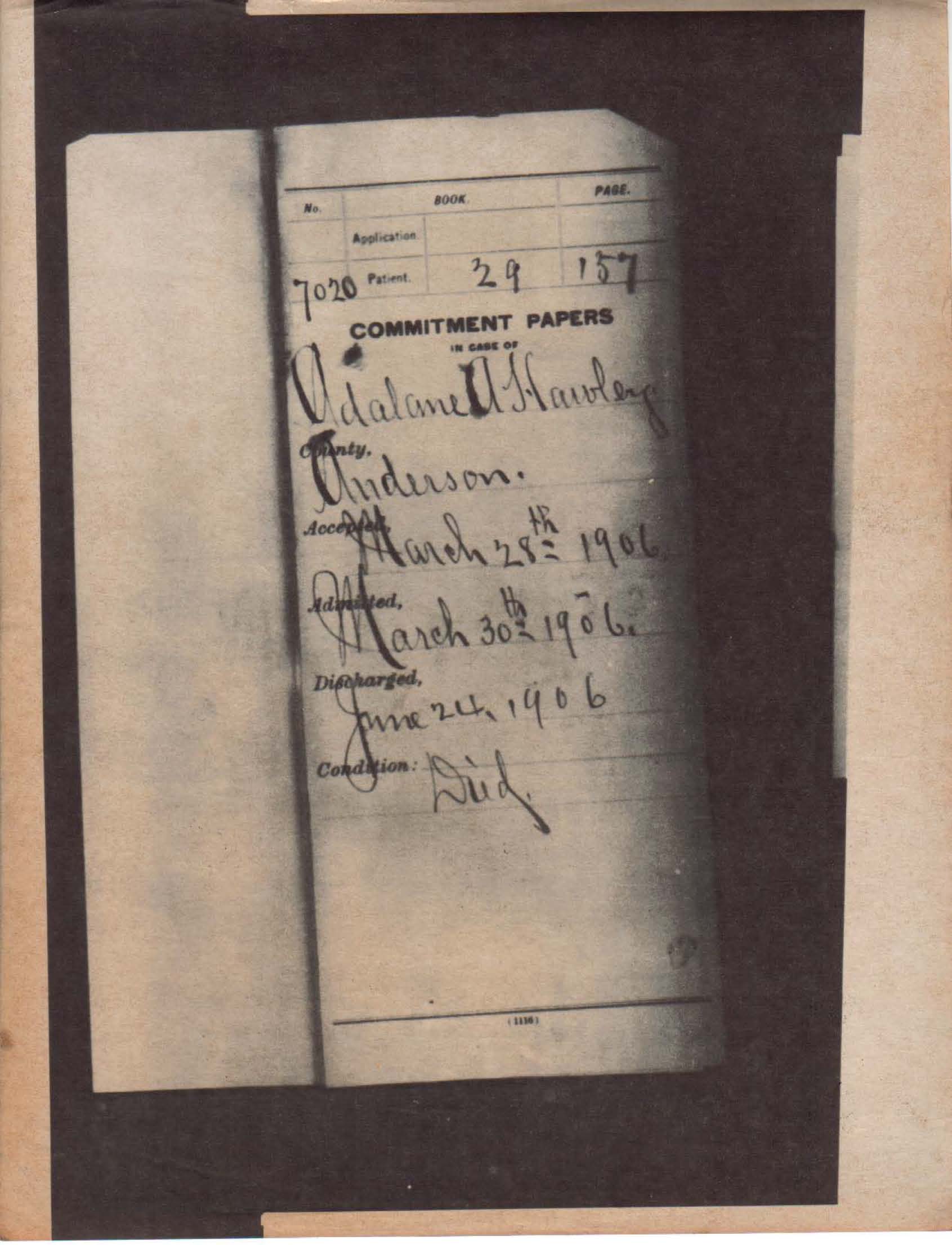

Martin Hawley, and sons. Commitment papers for Adelaide Hawley.

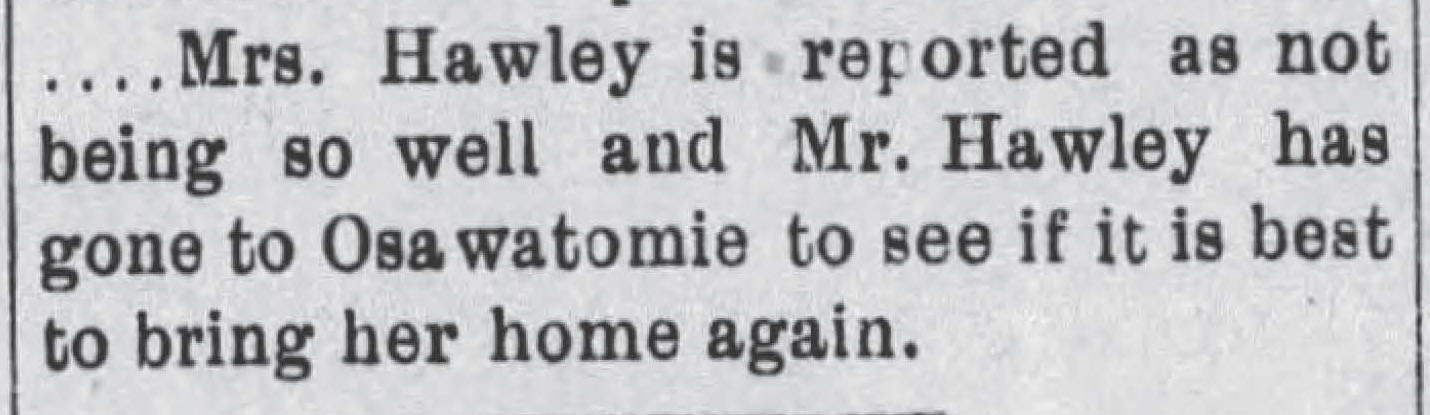

Commitment papers for Adelaide Hawley. The Journal-Plaindealer April 20, 1906.

The Journal-Plaindealer April 20, 1906. An article

from the Independent Review June 29, 1906.

An article

from the Independent Review June 29, 1906. The plot in Garnett Cemetery where Adelaide and Martin are buried

with no tombstone.

The plot in Garnett Cemetery where Adelaide and Martin are buried

with no tombstone. Overall treatment

Straightjacket, belt and shackles used to restrain violent patients

at the asylum until 1956. Photo: Osawatomie History Museum.

Straightjacket, belt and shackles used to restrain violent patients

at the asylum until 1956. Photo: Osawatomie History Museum. Closeup of the belt and shackles used to restrain violent patients

at the asylum until 1956. Photo: Osawatomie History Museum.

Closeup of the belt and shackles used to restrain violent patients

at the asylum until 1956. Photo: Osawatomie History Museum. Ted Hunter from the Osawatomie History Museum demonstrates a

broom that was used by inmates at the asylum to sweep the asylum floor.

Ted Hunter from the Osawatomie History Museum demonstrates a

broom that was used by inmates at the asylum to sweep the asylum floor.

Infirmary (1901 and 2019)

The infirmary in 1911.

The infirmary in 1911. The abandoned infirmary in 2019. Photo by P Marlin

The abandoned infirmary in 2019. Photo by P Marlin  The abandoned infirmary in 2019. Photo by P Marlin

The abandoned infirmary in 2019. Photo by P Marlin The south side of the abandoned infirmary in 2019.

Photo by P Marlin

The south side of the abandoned infirmary in 2019.

Photo by P MarlinAsylum Bridge and Brick Road (2019)

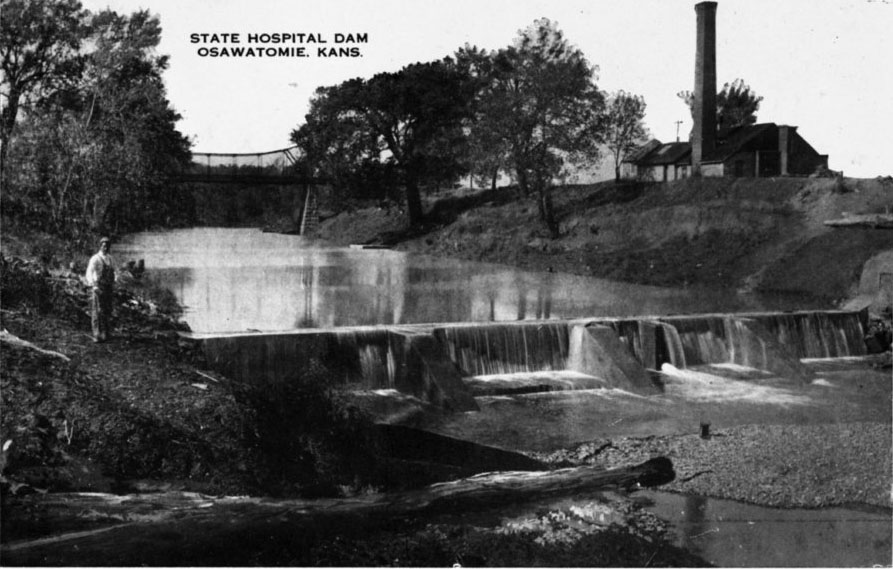

The hospital dam and asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River.

Kansas Memory

The hospital dam and asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River.

Kansas Memory The Osawatomie State Hospital asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River. The bridge is abandoned now, however, it once served

as the main thoroughfare from the town of Osawatomie to

the hospital and points north.

The Osawatomie State Hospital asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River. The bridge is abandoned now, however, it once served

as the main thoroughfare from the town of Osawatomie to

the hospital and points north. The Osawatomie State Hospital asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River. The bridge is abandoned, however, it served

as the main thoroughfare from the town of Osawatomie to

the hospital and points north.

The Osawatomie State Hospital asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River. The bridge is abandoned, however, it served

as the main thoroughfare from the town of Osawatomie to

the hospital and points north. The Osawatomie State Hospital asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River. The bridge is abandoned, however, it served

as the main thoroughfare from the town of Osawatomie to

the hospital and points north.

The Osawatomie State Hospital asylum bridge over the Marias des

Cygnes River. The bridge is abandoned, however, it served

as the main thoroughfare from the town of Osawatomie to

the hospital and points north. The original brick road. Photo by P Marlin 2019

The original brick road. Photo by P Marlin 2019 The original brick road. Photo by P Marlin 2019

The original brick road. Photo by P Marlin 2019Asylum Cemetery (2019)

List of OSH burials

People who are believed to have been patients at OSH

Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019

Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019 Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019

Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019 Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019

Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019 Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by D Marlin

2019

Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by D Marlin

2019 Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019

Osawatomie State Hospital Memorial Cemetery. Photo by P Marlin

2019“Old Main” and the Sunken Garden (2019)

Photo of the "Old Main" Kirkbride building with the sunken garden

in the forefront before the building was demolished in October 2002. Source: Old Main at

Osawatomie State Hospital.

Photo of the "Old Main" Kirkbride building with the sunken garden

in the forefront before the building was demolished in October 2002. Source: Old Main at

Osawatomie State Hospital. The same view in 2019. The "Old Main" is gone and the fountain and seating area (sunken garden)

is in fairly bad shape. Photo by P Marlin

.

The same view in 2019. The "Old Main" is gone and the fountain and seating area (sunken garden)

is in fairly bad shape. Photo by P Marlin

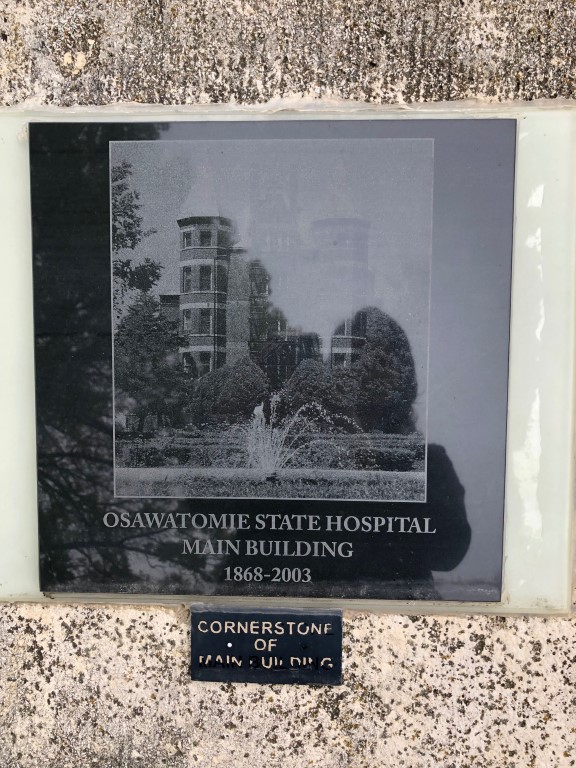

. The "Old Main" cornerstone monument. Photo by P Marlin

The "Old Main" cornerstone monument. Photo by P Marlin

The "Old Main" cornerstone monument. Photo by P Marlin

The "Old Main" cornerstone monument. Photo by P Marlin

The original stone entrance that passed through the sunken garden on the

way to "Old Main." Photo by P Marlin

The original stone entrance that passed through the sunken garden on the

way to "Old Main." Photo by P Marlin Me in the sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin

Me in the sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin  Sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin

Sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin  Sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin

Sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin  Sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin

Sunken garden. Photo by D Marlin D.O. Bacon's Art Gallery (2019)

Artist D.O. Bacon was admitted to the Asylum as a patient in 1900 at the age of 63.

Diagnosed with "sun or heat stroke," he spent the next two years in treatment.

While Bacon was at Old Main, a nurse gathered some old paints and

paintbrushes and allowed him to paint the walls. The mural, which consisted

of twenty-four pictures on two walls of his 7 X 11 foot room, is

thought to be reproductions of postcards and calendars.

Artist D.O. Bacon was admitted to the Asylum as a patient in 1900 at the age of 63.

Diagnosed with "sun or heat stroke," he spent the next two years in treatment.

While Bacon was at Old Main, a nurse gathered some old paints and

paintbrushes and allowed him to paint the walls. The mural, which consisted

of twenty-four pictures on two walls of his 7 X 11 foot room, is

thought to be reproductions of postcards and calendars. D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019 D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019

D.O. Bacon mural (1901) on display in the main administration

building of the Osawatomie State Hospital. Photo by P Marlin 2019Osawatomie State Hospital Relics (2019)

The Osawatomie History Museum which displayed

many Osawatomie State Hospital relics. Photo by P. Marlin 2019

The Osawatomie History Museum which displayed

many Osawatomie State Hospital relics. Photo by P. Marlin 2019 A display of old hospital relics. The ornate cabinet was

used in a previous superintendent's office. A bust of a former

superintendent sits on the cabinet. Photo by P. Marlin 2019

A display of old hospital relics. The ornate cabinet was

used in a previous superintendent's office. A bust of a former

superintendent sits on the cabinet. Photo by P. Marlin 2019 This spire once topped one of the south-facing twin towers.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019

This spire once topped one of the south-facing twin towers.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019 This spire once topped one of the south-facing twin towers.

The original road signs can be seen behind the spire.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019

This spire once topped one of the south-facing twin towers.

The original road signs can be seen behind the spire.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019 Nails from the "Old Main."

Photo by P. Marlin 2019

Nails from the "Old Main."

Photo by P. Marlin 2019 Osawatomie State Hospital Old Main doorknob and pass key.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019

Osawatomie State Hospital Old Main doorknob and pass key.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019 Christmas ornament with a depiction of the Historic Old Main

administration building. Photo by P. Marlin 2019

Christmas ornament with a depiction of the Historic Old Main

administration building. Photo by P. Marlin 2019 China dishes from the living quarters of the

superintendent in the days when they resided in the basement

of the Old Main. Photo by P. Marlin 2019

China dishes from the living quarters of the

superintendent in the days when they resided in the basement

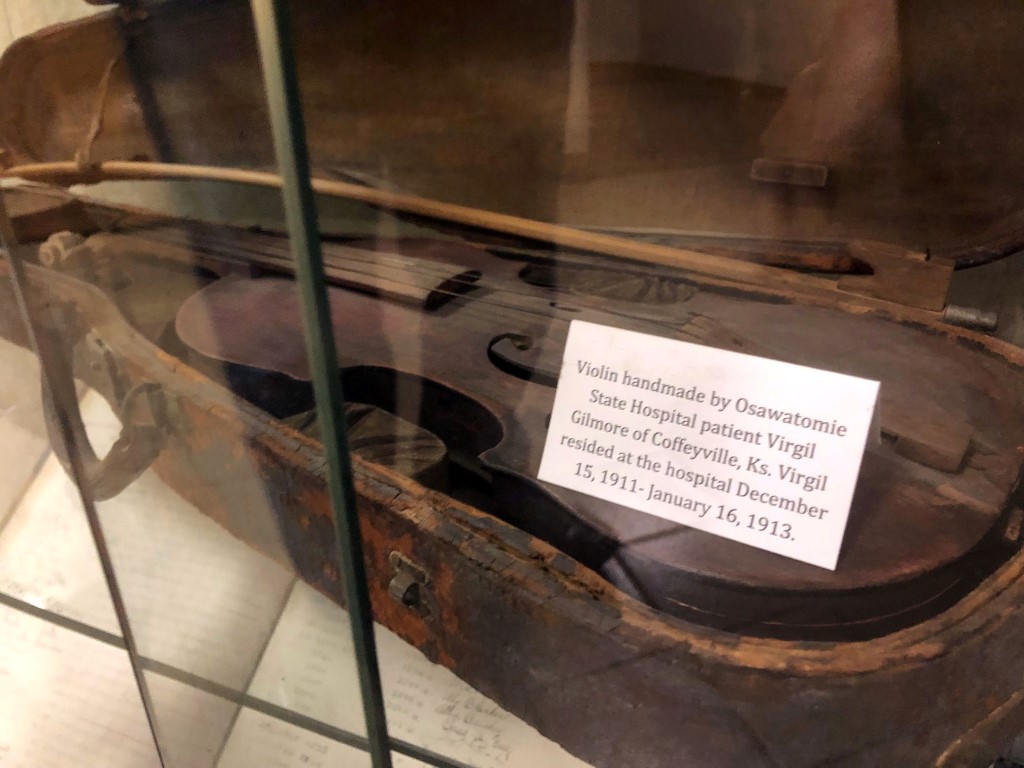

of the Old Main. Photo by P. Marlin 2019 Violin made by asylum patient Virgil Gilmore. Photo taken by

P Marlin at the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration Building display.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019

Violin made by asylum patient Virgil Gilmore. Photo taken by

P Marlin at the Osawatomie State Hospital Administration Building display.

Photo by P. Marlin 2019Sources

An attempt at humor in The Evening Herald (Ottawa, Kansas)

on June 27, 1914.

An attempt at humor in The Evening Herald (Ottawa, Kansas)

on June 27, 1914.