P. Marlin January 2021

Williamsburg was founded as the second capital of the Virginia Colony in 1699. The original capital, Jamestown, was the first permanent English-speaking settlement in the New World founded in 1607. Colonial leaders petitioned the Virginia Assembly to relocate the capital from Jamestown to Middle Plantation, five miles inland between the James and the York Rivers. The new city was renam ed Williamsburg in honor of England’s reigning monarch, King William III. In 1926, the Restoration of Williamsburg began when Rector of Bruton Parish Church, the Reverend Doctor W. A. R. Goodwin, brought the city's importance to the attention of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., who then funded and led the massive reconstruction of the eighteenth century city we see today.

"History enkindles the imagination of man and quickens his sense of reverence, thus prompting him to preserve the memorials of the creative past and enabling him to appreciate these memorials when he stands in their presence. The restoration of this colonial city, by making America more conscious of its heritage, will help to develop a more highly educated and consequently a more devoted spirit of patriotism." -W.A.R Goodwin 1

A Christmas wreath adorns the brick wall encircling the Bruton

Parish Church. Bruton Parish Church is the successor to the

church that was built soon after Middle Plantation was established.

P Marlin 2020

A Christmas wreath adorns the brick wall encircling the Bruton

Parish Church. Bruton Parish Church is the successor to the

church that was built soon after Middle Plantation was established.

P Marlin 2020

Christmas wreaths at the entrance gates to Bruton Parish

Church. P Marlin 2020

Christmas wreaths at the entrance gates to Bruton Parish

Church. P Marlin 2020

It was Christmas 1934, and the partially restored town of Williamsburg, Virginia, had only been open a few months. For the past five years, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., had been peeling away at layers of history to reveal the Williasmburg of the eighteenth century. As tourists walked up and down the Duke of Gloucester Street that Christmas, they were presented with a few live evergreens decorated with bright stands of colored lights. Thinking the effort was underwhelming, the staff of Colonial Williamburg began to research yuletide celebrations of colonial times with historical practices and decorations. Research into colonial letters, diaries, and documents, however, did not reveal much. 2

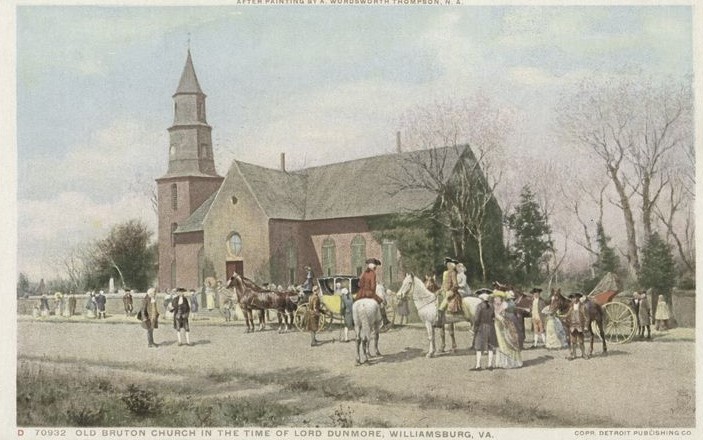

Bruton Parish Church in colonial times.

New York Public Library

Bruton Parish Church in colonial times.

New York Public Library

In the eighteenth century, as with English custom, Christmas season typically started on Christmas Eve and extended through Twelfth Night (January 6th). For the wealthy, this was a time of feasts, fox hunts, music and dancing. Those who were enslaved may have received rum or liquor and time off of work. Christmas decorations may have included evergreens in the church or mistletoe inside the house. Williamsburg shopkeepers placed ads noting items appropriate as holiday gifts, but New Year's was as likely a time as December 25 for bestowing gifts. The emphasis on Christmas as a magical time for children did not come about until the nineteenth century. Overall, Christmas during the eighteenth century was mostly a religious celebration with sumptuous feasts and time spent with family and friends. 2

Dancing colonial style during an eighteenth century Christmas.

Dancing colonial style during an eighteenth century Christmas.

Though not historically associated with Christmas, illuminations did occur during the colonial era. Typically, a single candle would be placed in public buildings and homes, sometimes in conjunction with a bonfire or fireworks to mark a major event. In 1702, at the ascension of Queen Anne, the windows of the Wren Building at the College of William and Mary were illuminated with candles. 2

Candles in the windows of the Ludwell-Paradise House situated

on Duke of Gloucester Street. P Marlin 2020

Candles in the windows of the Ludwell-Paradise House situated

on Duke of Gloucester Street. P Marlin 2020

The origins of what is referred to today as the Williamsburg -style Christmas, full of fruits, shells and magnolia, did not start in the eighteenth century, but in the twentieth. Louise Fisher, who in 1930 moved to Williamsburg, is credited with starting the decoration traditions that exist today. Without adequate eighteenth century references, Mrs. Fisher and her successors began to research English paintings and prints of the period, assuming English colonial residents would follow tradition and decorate with whatever winter greenery was available.2 3

Louise Fisher prepares a festive table centerpiece. 3

Louise Fisher prepares a festive table centerpiece. 3

Inspired by fifteenth and sixteenth century sculptors, Luca della Robbia and Grinling Gibbons, Mrs. Fisher began to make her plain green wreaths more festive. Italian garlands created in terra cotta and wood carvings displayed in English churches inspired Mrs. Fisher to use fruits in her arrangements. In an effort to keep within the bounds of American History, Mrs. Fisher used Robert Furber's prints to select only those fruits or plants known to have been available to colonial Virginians. Though by colonial standards, fruit was far too expensive to be used purely for decoration. By 1939, the "della Robbia" wreaths were attracting considerable attention and the "Williamsburg Christmas look" was launched.

An inspired Luca della

Robbia Madonna and Child piece.

Italian Pottery

An inspired Luca della

Robbia Madonna and Child piece.

Italian Pottery

A Robert Furber print.

A Robert Furber print.

A 1926 issue of House Beautiful illustrates Williamsburg's fruit-laden wreaths and explains, “Of late years, besides the staple wreaths of plain greens to which we have long been accustomed, the holiday's emblems have blossomed forth,--or perhaps we should say fruited forth,-- with richness of Grapes, brussel sprouts and ivy decorate the Charlton House color produced by the use of either natural or artificial fruit as an embellishment. This idea was undoubtedly suggested by the gorgeous Italian carvings and terra cottas of the Renaissance…” 4

Madonna and Child adorn one of the Williamsburg buildings

in 1968.

Madonna and Child adorn one of the Williamsburg buildings

in 1968.

Today, all-natural materials, including peppers and flowers harvested from the area gardens are dried for decorating use. The staff, with the help of volunteers, decorate more than 100 sites, including exhibition buildings, shops, houses and taverns. Historical trades sites create their own door decorations representing the shops. In Mrs. Fisher's day, the Christmas decoration would only be displayed for a week, however, today the wreaths stay up for up to six weeks. Maintenance of the wreaths with fruits must be changed out every other week to keep them looking crisp; they are also checked every day, and any repairs are made as needed.

Dried flowers with pine cones and greenery wreath decorates the door of Peter Hay’s Shop. P Marlin 2020

Dried flowers with pine cones and greenery wreath decorates the door of Peter Hay’s Shop. P Marlin 2020

A Christmas wreath of lemons and pomegranates. P Marlin 2020

A Christmas wreath of lemons and pomegranates. P Marlin 2020

An apple and magnolia leaf swag, as inspired by sculptor Gringling Gibbons. P Marlin 2020

An apple and magnolia leaf swag, as inspired by sculptor Gringling Gibbons. P Marlin 2020

The Robert Carter house in 1928. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Robert Carter house in 1928. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Robert Carter house in 2020. P Marlin 2020

The Robert Carter house in 2020. P Marlin 2020

A closer look at the oranges and dried flowers swag that hangs under the windows of the Robert Carter house. P Marlin 2020

A closer look at the oranges and dried flowers swag that hangs under the windows of the Robert Carter house. P Marlin 2020

A closer looks at the oranges and magnolia leaf wreath that hangs on the Robert Carter house. P Marlin 2020

A closer looks at the oranges and magnolia leaf wreath that hangs on the Robert Carter house. P Marlin 2020

The Governor's Palace was the official residence of the Royal Governors of the Colony of Virginia. It was also a home to two of Virginia's post-colonial governors, Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson. In addition to being the residence for the governors, the Palace was also used to host elegant balls, galas and other large events. In 1780, the government moved to Richmond making Thomas Jefferson the last governor to live in the Governor’s Palace.

In 1781, the Palace was made into a hospital for American soldiers wounded in the Battle of Yorktown. During the archaeological investigations in 1930, 158 skeletons were found, including two women. These investigations confirmed that the cemetery was indeed a Revolutionary War cemetery and that the 156 skeletons were white males of military age. These skeletal remains and some showed signs of wounds, broken sword points, and a fragment of a cannon ball was beneath the hip of one of the skeletons. In 1781, shortly after the surrender of the British at Yorktown, the Governor’s Palace was destroyed in a fire. 1

Servicemen pose in front of a decorated Governor's Palace during

Christmas 1941. John D. Rockefeller Library

Servicemen pose in front of a decorated Governor's Palace during

Christmas 1941. John D. Rockefeller Library

Christmas decorations at the Governor's Palace. P Marlin 2020

Christmas decorations at the Governor's Palace. P Marlin 2020

John Wayne strikes a

funny pose at the Governor's Palace during filming of the Perry

Como Christmas special in 1978.

John D. Rockefeller Library

John Wayne strikes a

funny pose at the Governor's Palace during filming of the Perry

Como Christmas special in 1978.

John D. Rockefeller Library

The John Blair House is one of the oldest buildings in Williamsburg. The right side of the house was built in 1720-1723, and the left side of the house was added in 1737. The house is named for John Blair Sr., a nephew of Reverend John Blair, minister of Bruton Parish Church and first president of the College of William and Mary. An interesting feature is the concrete steps with iron clasps, thought to be from the eighteenth Century.

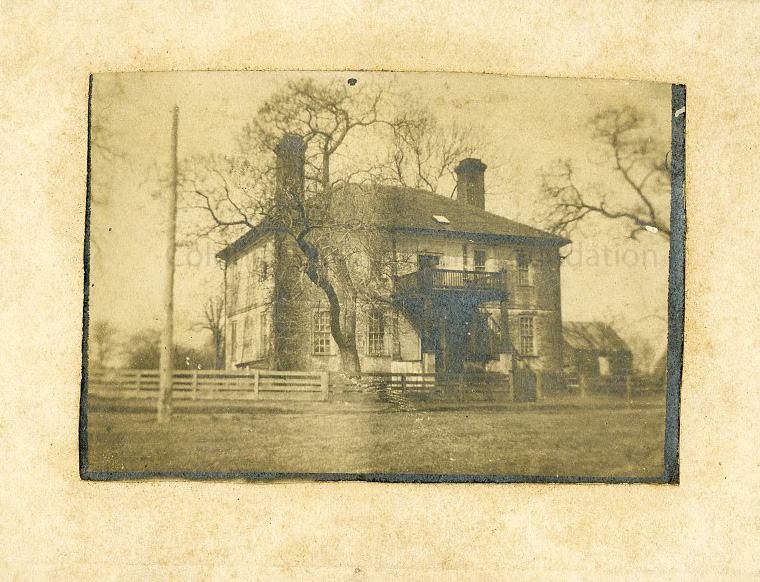

The John Blair house before renovation.

The John Blair house before renovation.

The John Blair house in 2020. Notice the steps. P Marlin 2020

The John Blair house in 2020. Notice the steps. P Marlin 2020

The John Blair House in miniature decorates the front door. P Marlin 2020

The John Blair House in miniature decorates the front door. P Marlin 2020

The John Blair house in 1720 miniature. P Marlin 2020

The John Blair house in 1720 miniature. P Marlin 2020

A close up of a dollhouse within the dollhouse. P Marlin 2020

A close up of a dollhouse within the dollhouse. P Marlin 2020

The Colonial Williamsburg Courthouse was constructed in 1770. Debtor's disputes with their creditors, complaints against pig stealers, and an apprentice's pleas for protection from an abusive master were the types of cases heard here. A whipping post and the public stocks stood just outside, a few steps from the prisoner's dock, for quick punishment. Slaves were tried for felonies by county courts under commissions of oyer and terminer. 3

The Courthouse served the Williamsburg community for more than 160 years, though business was interrupted briefly by the Civil War. In 1928, Colonial Williamsburg secured rights to the building, but local government used the property until 1932, when it closed for restoration.

The Williamsburg Courthouse in 1878. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Williamsburg Courthouse in 1878. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Courthouse decorated for Christmas.

P Marlin 2020

The Courthouse decorated for Christmas.

P Marlin 2020

Inside the Courthouse. P Marlin 2020.

Inside the Courthouse. P Marlin 2020.

The Wythe House is located along the Palace Green. Built in 1755, it was the home of George Wythe, signer of the Declaration of Independence, as well as scholar and teacher of Thomas Jefferson. Wythe was also the tutor of John Marshall, chief justice of the Supreme Court, and was the first professor of law at William and Mary College. George Washington used this house as his headquarters in 1781 before the seige of Yorktown. The house was reconstructed in 1939-40.

The George Wythe House in 1904. John D. Rockefeller Library

The George Wythe House in 1904. John D. Rockefeller Library

The George Wythe House in the mid 1930's. 1

The George Wythe House in the mid 1930's. 1

The George Wythe house Christmas decorations. P Marlin 2020

The George Wythe house Christmas decorations. P Marlin 2020

Christmas decorations of apples and greenery. P Marlin 2020

Christmas decorations of apples and greenery. P Marlin 2020

A wreath on one of the George Wythe house outbuildings features

shells, peppers, and artichokes. P Marlin 2020

A wreath on one of the George Wythe house outbuildings features

shells, peppers, and artichokes. P Marlin 2020

A wreath on one of the George Wythe house outbuildings. P Marlin 2020

A wreath on one of the George Wythe house outbuildings. P Marlin 2020

Thomas Everard, Mayor of Williamsburg, purchased this house in the mid 1750s. In the 1770s, Everard showed his support of Virginia's move toward independence by signing the 1770 Non-Importation agreement and by serving on the committee to elect Virginia's delegates to the Continental Congress. Everard served in several capacities, clerk of the York County court, deputy clerk of the General Court, clerk of the Secretary of the Colony's office, and mayor of Williamsburg serving twice from 1766 to 1767 and 1771 to 1772.

Pre-restoration view of the Thomas Everard House, 1907, from a Rees Stereograph

Produced by Henry E. Rees, Hartford, CT, 1907.

Pre-restoration view of the Thomas Everard House, 1907, from a Rees Stereograph

Produced by Henry E. Rees, Hartford, CT, 1907.

Thomas Everard house decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

Thomas Everard house decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

A close up of the wreath that adorns the Thomas Everard front door,

a replica of a court document signed by him. P Marlin 2020

A close up of the wreath that adorns the Thomas Everard front door,

a replica of a court document signed by him. P Marlin 2020

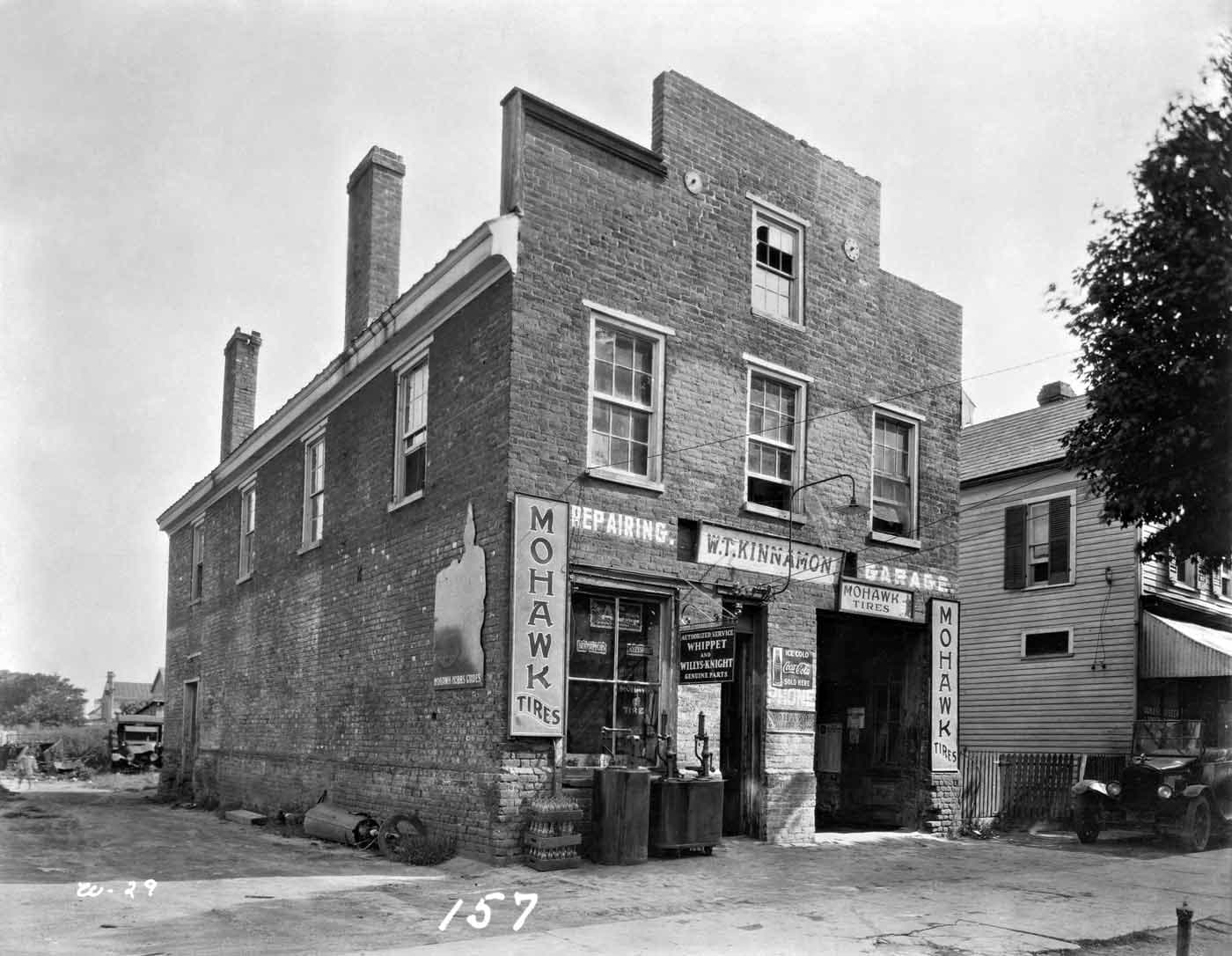

A milliner is a hatmaker. It was to this profession that Margaret Hunter, newly arrived from London, set up shop in Williamsburg. Originally constructed in 1737, the brick building owned by Margaret Hunter from 1774 to 1787, had become Kinnamon’s store by the time it was purchased by John D. Rockefeller, Jr. as part of Williamsburg’s Restoration. The first photo below documents the building's appearance in 1926. Today, the shop has been brought back to its mid-1700s appearance. 5

Kinnamon's Store. John D. Rockefeller Library

Kinnamon's Store. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Margaret Hunter Milliner Shop decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

The Margaret Hunter Milliner Shop decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

Bassett Hall was built between 1753 and 1766 by House of Burgesses' member Philip Johnson. It was purchased around 1800 by Virginia legislator and congressman Burwell Bassett, a nephew of Martha Washington.

In 1926, John D. Rockefeller Jr. was inspired by the vision of Rev. Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, of Bruton Parish Church, to restore Williamsburg to its eighteenth century appearance. At that time, the Rockefellers began their generous financial support for this complex project and soon acquired Bassett Hall, where they would reside while in Williamsburg to oversee the progress of the decades-long Restoration.

Bassett Hall in 1928. John D. Rockefeller Library

Bassett Hall in 1928. John D. Rockefeller Library

Bassett Hall. P Marlin 2020

Bassett Hall. P Marlin 2020

The gates to Bassett Hall decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

The gates to Bassett Hall decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

The Elkanah Deane House is located just steps away from the Governor's House. Elkanah Deane, the home's namesake, was a coach maker who immigrated to Williamsburg from Ireland during eighteenth century. He purchased the home in 1772. Hence, the horseshoe on the wreaths.

The Elkanah Deane House in 1938. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Elkanah Deane House in 1938. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Elkanah Deane House. P Marlin 2020

The Elkanah Deane House. P Marlin 2020

A closer look at the horseshoe wreath. P Marlin 2020

A closer look at the horseshoe wreath. P Marlin 2020

John Custis, politician and a member of the Governor's Council the Colony of Virginia, built this house in 1717. The Custis -Maupin House was often leased as a tenement. Owned by the Maupin family in the nineteenty century, the house was reconstructed in 1932.

The Custis-Maupin House in 1931. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Custis-Maupin House in 1931. John D. Rockefeller Library

The Custis-Maupin House at night. P Marlin 2020

The Custis-Maupin House at night. P Marlin 2020

Christmas wreaths with apples. P Marlin 2020

Christmas wreaths with apples. P Marlin 2020

The College of William and Mary was founded in 1693 by the royal charter of King William III and Queen Mary II of England. William & Mary is the second oldest institution of higher learning in the United States (after Harvard). One of the university's principal halls, the Sir Christopher Wren Building, is one of the oldest college buildings still in use in America.

The College became the alma mater of three United States presidents, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and John Tyler. Though not a student, George Washington came to the College to take the required examination before the professor of mathematics and to be commissioned a county surveyor.1

There is a crypt under the Wren Building chapel containing the remains of Lord Botetourt (statue) and Peyton Randolph, first President of the Continental Congress.

Though the Wren Building has burned several times, the walls are original.

The Wren Building at the College of William and Mary in 1858.

The Wren Building at the College of William and Mary in 1858.

The Wren Building in 2020 with the statue of Royal Governor of Virginia,

Lord Botetourt, holding a Christmas wreath. P Marlin 2020

The Wren Building in 2020 with the statue of Royal Governor of Virginia,

Lord Botetourt, holding a Christmas wreath. P Marlin 2020

Lord Botetourt holds a Christmas wreath. P Marlin 2020

Lord Botetourt holds a Christmas wreath. P Marlin 2020

An unknown building whose wreaths indicate a schoolhouse. P Marlin 2020

An unknown building whose wreaths indicate a schoolhouse. P Marlin 2020

"Wanted: A sober, diligent schoolmaster." P Marlin

2020

"Wanted: A sober, diligent schoolmaster." P Marlin

2020

A reading wreath. P Marlin 2020

A reading wreath. P Marlin 2020

Near the center of town was a spacious open green designated as Market Square. In 1749, the historic Market Square Tavern was established. The Tavern was also home to Thomas Jefferson during the time of his law studies with George Wythe.

Market Square Tavern before reconstruction. John D. Rockefeller Library

Market Square Tavern before reconstruction. John D. Rockefeller Library

Market Square Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Market Square Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Market Square Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Market Square Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Market Square Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Market Square Tavern. P Marlin 2020

In 1738, Henry Wetherbum purchased two lots across the street from the Raleigh Tavern. He began to build a house on the lots. In 1742, a group of men purchased the Raleigh Tavern, where Wetherburn had been working as the tavern keeper. Wetherburn decided to move across the street and open his own tavern in his house.

Wetherburn Tavern in 1928. John D. Rockefeller Library

Wetherburn Tavern in 1928. John D. Rockefeller Library

Wetherburn Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Wetherburn Tavern. P Marlin 2020

The Raleigh Tavern, established in 1717, long served as a focal point in colonial life. Named after the founder of the Virginia colony, Sir Walter Raleigh, it was the sight of a great many balls, banquets, community meetings, and business gatherings.

It was here that the royal governers were banqueted upon their arrival from England; here, George Washington, according to his diary, frequently dined (in the Daphne Room); and it was here that Thomas Jefferson danced with his "Fair Belinda." The original Raleigh Tavern structure survived until 1859, when it burned down. It was reconstructed in 1930-31.

Raleigh Tavern in 1928. P Marlin 2020

Raleigh Tavern in 1928. P Marlin 2020

Raleigh Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Raleigh Tavern. P Marlin 2020

Merchant's Square is a shopping area adjacent to the College of Williams & Mary created in the mid-1930s.

Merchant's Square in early years. John D. Rockefeller Library

Merchant's Square in early years. John D. Rockefeller Library

Merchant's Square decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

Merchant's Square decorated for Christmas. P Marlin 2020

The Music Shop. P Marlin 2020

The Music Shop. P Marlin 2020

The Printer's Shop. P Marlin 2020

The Printer's Shop. P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

P Marlin 2020

A masked doll in a Williamsburg shop represents a pandemic year. P Marlin 2020

A masked doll in a Williamsburg shop represents a pandemic year. P Marlin 2020

1 "The Restoration of Colonial Williamsburg." National Geographic April 1937

2 Oliver, Libbey Hodges and Theobald, Mary Wiley. Colonial Williamsburg. New York, NY, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1999.

3 Colonial Williamsburg: Budding Style

4 Colonial Williamsburg: Deck the Doors